“But I am certain of what is false and what is sacred,

“But I am certain of what is false and what is sacred,

I understood it all a long time ago.

My way is straight, just straight, guys,

And luckily there is no other choice!”

-Vladimir Vysotsky

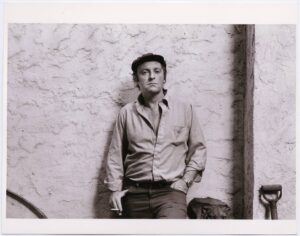

Vladimir Vysotsky (1938-1980) was one of the greatest bards in Russian history whose influence and popularity among Russian people during the second half of the 20th century was unprecedented. It is still not understood in full, even now more than 40 years after his death. Vladimir Vysotsky was an actor and a balladeer; he wrote and sang his own songs, always with a guitar, in the Russian genre of bard poetry. As Vysotsky himself explained it to the audience: “I write author’s songs and I believe them to be a specific genre. Generally speaking, they are not songs but poems on a rhythmical base…The point is that author’s songs give me a chance to tell what worries me, what is of concern to me, that sort of thing.”(1)

What was so unusual about the balladeer Vysotsky’s music and personality that made his songs the voice of the Russian soul and himself a true folk hero? He had no official status as a poet in the official Soviet hierarchy, as if he were completely invisible in the eyes of the authorities. He was not a member of the Writer’s Union, and did not belong to the official establishment, which would usually generate prestige and money. He sang his ballads in his free time and traveled, giving concerts all around the Soviet Union. But his voice is still alive in recordings and Russians continue to mourn the great bard who wrote to Russian people: “People! I loved you! Be merciful!“(2)

Youth

Where are your seventeen years?

On Bolshoi Karetnoi.

Where are your seventeen troubles?

On Bolshoi Karetnoi.

Where is your black revolver?

On Bolshoi Karetnoi.

And where are you not today?

On Bolshoi Karetnoi.

Vysotsky was born in Moscow on January 25, 1938 in the family of a military officer. As a child, he spent several years in Eastern Germany with his father’s family. After his return to Russia, he lived in the hideous creation of the Soviet regime, the communal apartment, with several other families on Bolshoi Karetnoi Street. He studied at an actors’ school, and after his graduation worked as an actor in several theaters. The famous director Lyubimov took him on as an actor in the Moscow Theatre of Drama and Comedy on Taganka in 1964. In 1971, Vysotsky received the role of Hamlet and played it till his death. Well-liked by the public, he never received any official recognition. His salary of 170 rubles at the theater was not even enough to pay for the rent. He also played various movie and television roles, among them captain Zheglov in the popular serial Mesto vstrechi izmenit nelzia (1979).

But as he had told in the interview at Pyatigorsk TV studio in 1979, the poetry meant for him more than “anything else: “Mostly inspiration comes to me, usually at night… when I’m working on poems. As long as I live, as long as I think, I will of course write poems, write songs.” (3)

He started to write and sing songs as a student in the 60’s. It was his “courtyard hooligan” songs which made him famous very fast. (4) By 1967 the entire country already knew about Vysotsky. Sometimes there were the dubious texts, but their simplicity and humor made them popular very quickly:

I happened to be walking around

And I hurt two people by chance,

They took me to militia grounds

Where I saw her…and broke down at once.

At the beginning, they were songs written for his friends. As Vysotsky explained: “I began with songs that were called by many street songs or even gutter songs (blatnoi) for some reason. Doing so, I paid tribute to the urban romance. Generally speaking, when I began to write my songs, I had no idea that I would write for such an audience as I have now – in great halls, palaces and stadiums. In those days my songs were intended for a narrow circle of very close friends. We were a bunch of students then…the atmosphere was one of trust, complete ease, and what is most important friendliness”( 5).

Among his close friends at that time were Igor Kochanovskii, Andrei Tarkovskii, Oleg Strizhenov, Lev Kocharian, Vasilii Shukshin; all of them became actors and writers. Later, appeared friends who would stay with him for his entire life, the actor Vsevolod Abdulov and the artist Michail Shemiakin. And among them the young Vysotsky sang:

I was the soul of bad company.

And I can tell you, that

My last, first and middle names

Were well known to the KGB. (6)

Indeed, the company spent a lot of time drinking, singing songs, and wandering through public parks, and from that time Vysotsky became addicted to alcohol.

There would be more of them in the future: songs about criminals, workers, athletes and scientists, even about animals – dozens of them – written with such grace and humor that they quickly spread among listeners. It became an unrivaled encyclopedia of Russian urban life in the middle of 20th century embodied in the poetic form.

Russian Bard

Some critics view his poetry as a phenomenon of Soviet mass culture, based on the incorporation of Vysotsky’s phraseology into everyday Russian language. The characters from his songs and their vocabulary became a prominent feature of the linguistic scene in Russia. (7)

But who was Vladimir Vysotsky for the Russian people and for Russian culture in general? The bard’s influence on Russian mass culture in the the second half of the twentieth century was enormous, not just that of a singer or poet, it definitely went beyond the limits of mass culture. It was much more complex and touched the very nerve of the Russian soul at the end of the Soviet era.

His friend, the artist Mikhail Shemiakin, expressed this idea very clearly: “Vysotsky was a great poet… He did what no one before him had done – a synthesis of the absolutely reckless Russian soul with the clear abstract thinking of a brilliant philosopher.”(8)

The transformation from actor to great bard did not happen immediately, but was the result of many factors that influenced Vysotsky in the 1970s. Russian post-war society at the time was in a deep ideological and moral crisis. The emergence of Vysotsky, who had extraordinary charisma, tremendous talent, a strong personality, and most importantly, spoke the truth in his songs, gave Russians a cultural hero.

However, only by considering Vysotsky’s ability as a poet to penetrate to the depths of the human soul and “bring to the surface eternal themes” of humanity can we get an explanation for the great love that ordinary Russian people felt for him. Sometimes it was his immense humor provoking laughter or his reckless nature sounded in the songs, but it were always the words of truth. Vysotsky said in one of his songs: “I do not lie by any of my words” and considered himself as the servant of the pure Word. Yuri Andreev wrote that Vysotsky’s songs, in their fundamental essence, were” the assertion of the prevalence of the good in life and in every person“, and of the “overthrow of evil of any kind even at the price of one’s own life”.

Everything around Vysotsky was extraordinary, especially his ability to connect to ordinary people and to evoke a sense of trust. As Shemiakin remembered: “Volodya [Vysotsky] wrote about everything. He had never been at war, never did time in the camps, and never hacked at coal in the mines. But he has sensed everything vividly, and this emotion combined with the great poetic genius deeply touched the soul of the former warriors, prisoners…His entire work is that of one of the greatest analysts of the Russian land.“(9)

This young man carrying a guitar could potentially be seen anywhere in the Soviet Union, including Siberia and the Far East. He sang his songs, talked to people, and somehow during his journey he understood very important things about his country and the human soul. Most importantly, his poetic genius permitted him to embody this knowledge into his songs. In doing this, he succeeded in bringing his understanding at a very high level of communication. Vysotsky’s struggle to bring the words of goodness to the world was one of epic proportions and as a tribute to the great bard we should say that he succeeded.

Political Vysotsky

As Vysotsky became older, the themes of his songs changed with him. From the end of 60’s, the “hooligan” Vysotsky gave place to the analyst Vysotsky, a citizen of his country and a warrior. He made the progress extraordinarily swift. His songs evolved into complex ballads creating a panorama of Russian life. Vysotsky’s poetic universe consisted of thousands of characters, put into different situations, struggling and loving, suffering and laughing. It included fairy tales and war stories, ballads and parables. With the analytical eye of a thinker he recognized the disconnected state of his country. His poetic genius allowed him put the feelings of many into words.

Much was written about his travelings around Russia. It had stimulated his growth as an artist and as a public figure in Soviet society. What he understood during his contacts with the people, he was determined to bring to his listeners. Vysotsky said once: “I believe that these songs became so well-known precisely because of the desire to tell something very important, that’s why people listen to them, that’s why they are drawn to them”. His songs were powerful because they could explain the true nature of the current state of the Soviet Union to anyone:

It’s my fate till the end, till the cross,

Shout till I’m coarse, after that only numb,

To pursue and argue, till the mouth has froth,

That it’s all wrong, that it’s not right!

That the hucksters are lying about Christ’s mistakes,

That until the flagstone would press into dirt,

Three hundred years under the Tartar yoke were all a waste,

That was just it – hundreds years of indigence and shame.

But there was Ivan Kalita who did what he could,

And not only one but many who stood up to all,

The sweat of goodwill and the revolts in vain.

Pugachov, blood, and misery again…

Let the people not get it at first,

I’ll repeat it again even in the image of a fool.

But sometimes even the theme isn’t worth it,

And the vanity is the same old vain…

I am breaking my nerve, guys, to do what I can,

And someday one of you may for me light a candle,

For the naked nerves’ sting as I sing and I choke,

For the jolly manner in which I am joking…

“Was he Soviet or anti-Soviet? We did not discuss it with him. Most accurately, he was neither…. He simply could not tolerate unfairness and evil in any form “ (10).

Vysotsky often used metaphors in his songs: The Parable of the Truth and Lie, Wolf Hunt (1968), The Old House (1969), The Apples of Paradise (1973), but the listeners usually understood the true meaning within the songs. In 1975 he wrote Kupola (The Domes) – his prayer for Russia, which he devoted to Mikhail Shemiakin.

His songs were accepted by the Russian people as desperately needed words of truth about themselves, about the society in which they lived, about their hope and desperation, and about philosophical problems of the fate of individuals. It was never about abstract ideas, but always the personal choice between good and evil.

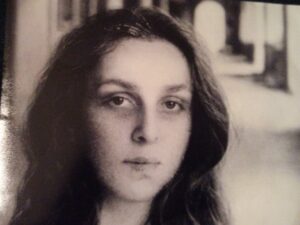

Marina Vlady

Marina Vlady

I would not compare anyone with you.

Even kill, shoot me for that!

Look how I am admiring you

Like the Madonna of Rafael!

It was like a gift from above to Vysotsky that, in the midst of his popularity as an actor and bard, among all turbulence of his life, in 1968 he met Marina Vlady, a beautiful French actress of Russian origin. Marina became his soul mate. They were married in 1970; it was the third marriage for both of them. Their life together was described in Marina’s memoir Vladimir or the Interrupted Flight; it was one of the poignant love stories of the 20th century. Marina was his guardian angel until his death. A lot was said about her by the Russian media, but her love had kept him alive for twelve years.

Interrupted Flight

With smiles they were breaking my wings,

My scream sometimes was like a wail.

And I was numb from pain and helplessness,

And could just whisper: thanks to be alive!

Who were “they” in this famous song? During his lifetime, the authorities’ oppression of Vysotsky was tremendous. As the actor Bortnik from Taganka remembered, it seemed as though the invisible evil of Soviet empire was trying to suffocate Vysotsky at every level (11). Marina wrote that his poems have never been published in Russia during his life; his songs were removed from soundtracks, his concerts canceled, his book and record deals revoked at the last moment.

His humor and ability to laugh through the most difficult times as well as the connection with the ordinary people from all corners of the Soviet Union helped him to overcome the failures but the level of stress was enormous.

What Vysotsky did in these conditions would not have been possible for anybody else: over thirteen years he held more than 500 personal concerts in the Soviet Union. From 1973 he started traveling abroad, first to France and Europe, then to the USA in 1978 and 1979, Canada and other countries. In New York he met with Joseph Brodsky and two of them spent a lot of time together. Ironically, the meeting of two last greatest Russian poets of the 20th century happened in America.

The repression only added to his charisma in the eyes of the Russian people, who saw the sole hero against the oppressive regime. During his last years he had all the moral and material support of the Russian people: it was not possible for the authorities to either expel him or silence him. But “it was his unusual, suffering, vulnerable soul” – according to Shemiakin’s words – “that made him suffer because of all the unjustness he saw in the world.” In 1972 he wrote one of his most tragic songs, Capricious Horses, full of reflection on the fate of the individual.

The wave of popularity and the material success of the preceding years did not mean a lot to him. Excessive oppression, stress, and addiction led to his early death. Vysotsky died on July 25th during the Moscow Olympic Games. The authorities did not write a word about his death, but people somehow found out and several hundred thousand people came to bid their farewell to him.

Vysotsky stated in his last poem to Marina in summer 1980 that his mission in life was fulfilled:

…I have a lot to sing to the Almighty.

I have my songs to justify my life”

By Elena Dimov.

Translations of the poems by Oleg Dimov

Resources and collection of Vysotsky’s songs

http://www.kulichki.com/vv

Britannica about Vysotsky

Capricious horses

Along the ledge, on a brink of a precipice.

I lash my horses, drive them on.

Somehow the air is not enough for me,

I drink the wind, I swallow the fog,

Feeling with a reckless delight, that I am vanishing, vanishing.

Slow down my horses, slow down!

Don’t listen the tight whip!

But somehow I got the capricious horses –

I didn’t finish living; I will not end my song.

I will let my horses drink water,

I will finish sing my verse.

For a moment, somehow I will stand

on the edge….

I will go like a feather from a hand – the hurricane will sweep me,

And the galloping horses will pull my sleigh on the morning snow.

Pace yourselves, my horses, do not hurry,

Let my last way to the shelter will be longer, just a little!

Slow down, my horses slow down!

The whip and lash are not your overseers!

But somehow I got the capricious horses –

I didn’t finish living; I will not end my song.

I will let my horses drink water,

I will finish sing my verse.

For a moment, somehow I will stand

on the edge. We’ve come in time: no late comings to God, –

Why then angels sing with such vicious voices?

Or is it a ringing bell got numb from sobbing?

Or is it me, crying to the horses not to carry the sleigh so fast?!

Slow down my horses, slow down!

I beg you, do not ran at such fast pace!

But somehow I got the capricious horses –

I didn’t finish living; I will not end my song.

I will let my horses drink water,

I will finish sing my verse.

For a moment, somehow I will stand

on the edge.

Notes:

1. Vladimir Vysotsky. On My Songwriting. In: Hamlet with a Guitar. Tr.by Sergei Roy. Moscow, 1990, pp.201, 203.

2.Vladimir Vysotsky. Pesni i stikhi. V.2. New York, 1983, p.140.

3.Vladimir Vysotsky: Poet,Chelovek.Aktior. M., 1990.

4.Cherniavsky, G. I. Politics in Poetry of the Great bards. “Russian Studies in Literature”, vol.41, no.1, Winter 2004-5. p.63-65.

5.Hamlet…pp.203-204.

6.Resources and collection of Vysotsky’s songs http://www.kulichki.com/vv

7.Hamlet... pp. 10-11.

8. Vladimir Vysotsky. Vse ne tak. Memorialnii almanakh-antalogia. Moscow, 1991, p.42.

9. Hamlet... p. 315

10. Vladimir Vysotsky v zapisiah Michaila Shemikina. N.Y., 1987. p.67.

11. Vse ne tak. Moscow, 1991, p.36