“Listen, my boon brethren and my enemies!

What I’ve done, I’ve done not for fame or memories

In this era of radio-waves and cinemas,

But for the sake of my native tongue and letters !”

1972

— Joseph Brodsky

Translated by Alan Myers with the author

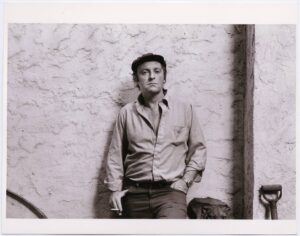

The name of the last great Russian romantic poet of the 20th century, Joseph Brodsky, hardly requires an introduction. His life in exile after his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1972 became a story of success; in 1987 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, became the Poet Laureate of the United States in 1991, and published numerous books of poems and essays. Today, Brodsky is considered one of the greatest romantic poets of the 20th century and has gone into the annals of 20th century world literature.

His whole life, however, was divided in two – before and after his expulsion – and the success of the last years of his life seems to overshadow the beginning, the life and poetry of a rebellious youth in the Soviet Union, where the right to be a poet was denied to him.

One can now look at his early poems with bewilderment at how they had already demonstrated the strength and ability of his powerful talent. Notably, Brodsky himself explained the nature of poetry to a judge at his infamous trial in 1964. When asked whether he studied to be a poet, he answered very simply: “I did not think you could get this from school.” The judge replied “But how, then?” and Brodsky said “I think it … comes from God…”(The Trial of Iosif Brodsky, A Transcript. The New Leader, Aug.31, 1964).

At the origin of Joseph Brodsky’s destiny was not the famous trial or the expulsion from the Soviet Union, as described in numerous works, but rather the gift of poetry, which he accepted with great humility. Joseph Brodsky told his friend Losev: “Poetry is when you start to write, one word leads to another.” And this gift came to Brodsky quite unexpectedly in 1958 or 1959. During a conversation with Solomon Volkov, he recalled how someone showed him a book by Vladimir Btitanishsky: “Well, I thought, surely someone could write better on this subject. So I started to write something myself, and that’s how it all began” (Volkov, S. Conversations with Joseph Brodsky. N.Y., 1998, p.32.).

Brodsky was born in Leningrad in May 1940 to a Jewish family. Joseph was their only child and the family was not prosperous; his father worked as a photographer and his mother was an accountant. Brodsky recalled: “Sometimes my father had work and sometimes he didn’t. Those were the times, the troubled times.” They lived in the hideous creations of the Soviet regime – “communal” apartments – with several other families, which was typical of the time.

Brodsky’s earlier life was as normal as it could be in the Soviet Union, but as a teen he dropped out of school and started to do odd jobs as a worker in Leningrad as well as in geological expeditions all around the Soviet Union. It was an unusual and rebellious act at that time. The young Brodsky was never a conformist; even his appearance was extraordinary. According to his acquaintances he was a strong youth with red hair which appeared to burst as a flame on his head.

Brodsky’s earlier life was as normal as it could be in the Soviet Union, but as a teen he dropped out of school and started to do odd jobs as a worker in Leningrad as well as in geological expeditions all around the Soviet Union. It was an unusual and rebellious act at that time. The young Brodsky was never a conformist; even his appearance was extraordinary. According to his acquaintances he was a strong youth with red hair which appeared to burst as a flame on his head.

At that time Brodsky started to write poetry, often during the expeditions. Later, he never included his early poems in his selections in English. They were published by Pushkin Fund in Sochinenia Iosifa Brodskogo ( St.Petersburg, 1992), and then in Tallinn and in Russian selection Pisma Rimskomu drugu (2010). Among them are Pilgrims, The Garden, Goodbye and others.

Already in his first and not quite as polished poems one see the qualities that later became the marks of his lyric poetry: the strength and beauty of his feelings and emotions, intellect, and the fascinating ability to incorporate them into images of certain places; and the interrelations with his emotional and metaphysical inner universe. One of his early poems, The Garden, had poignant strophes that could be considered the leitmotif of his life:

O, how empty and silent you are

In the autumn’s twilight

how spectrally the garden’s transparence reigns,

where the leaves approach the earth

through the great attraction of the collapse.

O, how silent you are!

Doesn’t your destiny

foresee challenge in my fate,

and the rumble of the fruits, which have left you,

like the sound of the bells, is it not close to you?

Great garden!

Grant my words

the whirling of tree trunks, the whirling of the truth,

where I am shuffling through the winding branches

into the fall of the leaves, into the twilight of the resurrection.

O, how can I live

until the future spring

to your branches, to my soul in sorrow,

when all your fruits are gone

and only your emptiness is real.

No, I’ll leave!

Let the colossal carriages,

take me somewhere.

My low path and your high path –

now they are similarly vast.

Goodbye, my garden!

For how long? ..Forever.

Keep in yourself the silence of the daybreak,

Great garden, shredding the years

on the bitter idylls of the poet.

Translated by Elena Dimov and edited by Margarita Dimova

Brodsky was only twenty years old when he wrote The Garden, but it is a masterpiece full of metaphysical and philosophical reflections on the fate of a poet. His poetic language was already refined, and his inner universe correlated with the magnificent garden full of the moving sense of the distant future as a time of a separation from everything he loved. Later this theme would be developed into the poetic universe of Brodsky, as well described by modern critics, but in this early poem it is just a magic garden of life and poetry.

How could a poet of such extraordinary ability survive in the brutal world of Soviet reality? It is the mystery of the poetry in the face of the prose of the real life. Brodsky could transfer the outside world into philosophical and even metaphysical messages through his poetry and did it with the easiness and grace of the true romantic talent.

After The Garden it happened that Brodsky became a poet noticed by many, especially by Anna Akhmatova, who proclaimed him to be the greatest poet among their generation. Anna Akhmatova became his mentor and friend until the end of her life. The Garden was followed by several outstanding poems Christmas Romance, The Black Horse and Procession. Another of Brodsky’s poems, Pilgrims, (1960) became famous and popular with the intellectual public in Leningrad.

ЦГЛА фото

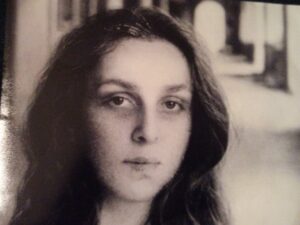

At this time, another fateful event in his life occurred: his meeting with Marina Basmanova, a young painter, the “enchantly silent and beautiful girl” (see:Gessen, Keith.The Gift. Joseph Brodsky and the Fortunes of Misfortune. The New Yorker, 2011, May 23). Their meeting and extravagant love affair inspired the most beautiful and poignant lyrical poems such as On Love (1971). Eighty of these were published by Brodsky in the collection New Stances to Augusta. Poems to M.B., 1962-1982, in 1983.

They never married, however, as another person became involved in their relationship: the poet Dmitry Bobishev, a friend of Brodsky’s, who appeared in the life of Marina Basmanova when Brodsky was especially vulnerable in 1963.

It was in November 1963 when an article was published in which Brodsky was ridiculed for almost everything: his poems, his appearance, and even his corduroy trousers. It was the beginning of the famous process which was ended by his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1972.

It was then that Brodsky knew about the affair. Brodsky was in a mental hospital in Moscow during New Year’s Eve and then, almost insane from jealousy and grief, went by train to Leningrad to confront Marina and Bobishev (The Gift). The escalation of the tension in his relationship with Basmanova continued until his arrest and exile to northern Russia in 1964.

Brodsky was arrested on February 11, 1964 on a street near his house. His parents did not know about the fate of their son for 24 hours. On February 18th, the process – which, according his friend and bibliographer Losev, was“ a reminisce of the Kafka’s process of presumed guilt in something that could not be defined “(Losev, Joseph Brodsky. Moscow, 1989, pp. 88-95) – started in the Dzerzhinsky district court in Leningrad.

The case was founded on the basis of the “social parasitism” of Brodsky (tuneadstvo) – a ridiculous article in Soviet law that allowed the arrest of almost anyone in the creative professions who was not a member of the official Union of Writers.

The case was founded on the basis of the “social parasitism” of Brodsky (tuneadstvo) – a ridiculous article in Soviet law that allowed the arrest of almost anyone in the creative professions who was not a member of the official Union of Writers.

It was surprising for such a young man – Brodsky was only 24 – to be so calm during the trial. The witnesses observed that nothing could distress Brodsky or overturn the absolute tranquility of his spirit in the face of the hostile trial. The level at which these two individuals, Brodsky and the judge, spoke revealed an absolute split between the spirit of the poet and the vulgar prose of the district court authority looking for petty criminals. The judge asked him “What are you doing for a living?” and the poet answered: “I write poems. I translate.” This was not accepted by the judge, and she repeated: “Do you have a permanent job?” – “I thought it is permanent job – to write poetry” – “Why you did not work?” And the poet answered: “I worked. I wrote poetry.” The judge: “What is your profession?” – Brodsky: “I am a poet” . “ Who recognized you as a poet? Who enrolled you in the ranks of poets? Brodsky: “No one. And who enrolled me in the ranks of humanity? Judge:” Did you study this?” – “This?” Judge: “To become a poet. You did not try to finish high school where they prepare, where they teach?” Brodsky: “I didn’t think you could get this from school”. Judge: “How then?” Brodsky: “I think that it . . . comes from God. (The New Leader, pp. 6-8). This dialogue is quintessential of the overall relationship between Brodsky and the state in the Soviet Union.

Between sessions of the trial, Brodsky was confined to a mental hospital again, where it was determined that he was psychologically fit to work. The sentence was short:

“The report of the Committee for Work with Young Writers demonstrates that Brodsky is not a poet. He was condemned by the readers of ” Evening Leningrad.” Therefore, in accordance with the decree of February 4, 1961, the court will send Brodsky to a distant location for a period of five years of forced labor”.

“The report of the Committee for Work with Young Writers demonstrates that Brodsky is not a poet. He was condemned by the readers of ” Evening Leningrad.” Therefore, in accordance with the decree of February 4, 1961, the court will send Brodsky to a distant location for a period of five years of forced labor”.

What could be more different than the mystical garden conceptualized by Brodsky and the pettiness of the authorities? In March 1964, he was sentenced to exile to northern Russia and spent 18 months in a labor camp near Archangelsk. He was released in 1966 after protests from the literary world.

Paradoxically, Brodsky remembered his exile as the happiest time of his life. At the same time, according to his friend Eugenii Rein, in Noreskaya Brodsky’s poetry took on a higher spiritual and metaphysical form.

His relationship with Marina continued sporadically; she came to visit him several times in his exile, and words from her meant much more for him than the activities of his release from the northern exile. In 1964 Brodsky wrote the poignant poem to M.B.: “In the darkness of night/baring hope’s powerlessness/mile by mile/love is backing away/from the mindlessness“.

He was released in 1966. In 1967 his son Andrei was born. However, his spiritual and intellectual conflict with the existing authorities escalated until the exile of 1972, leading to world infamy and the Nobel Prize in literature.

His relationship with Marina also deteriorated. Marina refused to give their son his last name choosing her own: Basmanov. In the spring of 1972, the authorities gave Brodsky three weeks to pack his bags and leave Russia. In 1972 he lost everything: his family, his friends, and his love, all at the same time. The Russian language in which he wrote his poetry became as distant as the fatherland, which expelled one of its greatest sons. Before leaving the USSR, Brodsky wrote in open letter to Brezhnev about his full assurance that he would come back to his motherland “in the flesh or on paper”: ‘even though my people don’t need my body, they still need my soul.”

His relationship with Marina also deteriorated. Marina refused to give their son his last name choosing her own: Basmanov. In the spring of 1972, the authorities gave Brodsky three weeks to pack his bags and leave Russia. In 1972 he lost everything: his family, his friends, and his love, all at the same time. The Russian language in which he wrote his poetry became as distant as the fatherland, which expelled one of its greatest sons. Before leaving the USSR, Brodsky wrote in open letter to Brezhnev about his full assurance that he would come back to his motherland “in the flesh or on paper”: ‘even though my people don’t need my body, they still need my soul.”

Brodsky never returned to Russia, nor did he see Marina Basmanova or his parents ever again. According to Losev, his son Andrei, came to visit him in New York once and this meeting did not bring a reconciliation. The poet Brodsky gradually gave way to his role as an essayist. The metaphorical verses of “The Garden” became true. He began to lose his great gift. In 1996, at the age of 55, Brodsky left this world.

Paradoxically, his poetry initially became more popular among the Western literary public then it was in the Soviet Union,0 where it was initially considered too cold and too intellectual. During his lifetime, he never became as loved by the Russian people as the other great poet, the bard Vladimir Vysotsky. Their relationship is yet to be analyzed: it is a different story. Brodsky touched on this indirectly in his Nobel lecture when he said that “there exists a rather widely held view, postulating that in his work a writer; in particular a poet should make use of the language of the crowd. For all its democratic appearance, and palpable advantages for a writer, this assertion is quite absurd.” (Nobel lectures from the Literature Laureates, 1986 to 2006. N.Y.-London, 2007, p.259

Joseph Brodsky never considered himself outside of his predecessors, the poets of the Silver Age. Among them were his mentor Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, and Marina Tsvetaeva. There are many epithets to describe the poet Brodsky: Intellectual, Exile, and Traveler. The magnificent garden of Brodsky’s poetry continues to attract the attention of readers.

From Outskirts to the Center

And then: no partitions.

Only a massive meeting,

as if someone from the darkness

is suddenly embracing us

and, full of darkness,

full of darkness and peace,

we all stand at the cold, gleaming river.

-Joseph Brodsky. Translated by Oleg Dimov and edited by Austin Smith

By Elena Dimov

Charlottesville, Virginia, 2011

Disclaimer

Pictures used: photo by Yakov Gordin, RIAF; Martha Pearson; film stills:”Иосиф Бродский – Возвращение,” Документальный фильм, Россия, 2010. Авторы Алексей Шишов; “Joseph Brodsky: In the Prison of Latitudes.” Documentary by Jan Andrews, Anny Carraro, Italy, USA, 2010.

The University of Virginia library has a rich collection of Brodsky’s poetry in English and Russian.

Other Resources: Library of Congress Online Resources

One thought on “The Magnificent Garden of Brodsky”