Now, in the second decade of the 21st century, we are witnessing an amazing renaissance of Russian free verse poetry, or poetry written, as Thomas Elliot defined it, “in the absence of traditional pattern, rhyme or meter” (Elliot). This unexpected phenomenon seems to have gone beyond the traditional Russian poetic narrative and has already provoked a heated debate among scholars, critics, and poets about its nature and the boundaries between free verse and cut prose, blank verse and rhymed verse, etc. (Manin 580-596). The purpose of this essay is to describe some features of contemporary Russian vers libre poetry as part of the ongoing process of development of the Russian poetic language in the era of new challenges.

To be precise, free verse is not a new phenomenon in Russian poetry. It appeared much earlier, in the 19th century, following Western literary trends, and was exemplified by the poets of the Silver Age until it was banned under Bolshevik rule in the 1920s. Underrepresented and marginalized in Soviet times, free verse has broken into the mainstream of the Russian poetic scene since the late 1990s. Once banned, free verse became one of the most popular hallmarks of Russian poetry in the 2000s and is now published by numerous literary magazines and websites. Twenty-five festivals, representing a wide range of poetic voices, were held in different Russian cities between 1990 and 2018, resulting in the publication of an anthology in 2020 (Sovremennyi russkii svobodnyi stikh. Antologia po materialam Festivalei svobodnogo stikha ). All this allows some critics to state that at the beginning of the 21st century it has established itself as “the dominant verse form in Russian poetry” (Orlitskaia 223).

This success is an indication of the great demand for this type of poetry in the Russian literary scene. In fact, its volatility seems to correspond to the new cultural trends in Russian society. The epochal change in Russian culture at the beginning of the twenty-first century reflects the end of the period of post-totalitarian mourning and the transition to a postmodern society. It has many dimensions in Russian culture, society, education, art, and literature. The concept of “new literature” has yet to be evaluated. However, it is clear that it includes changes in the genre structure of Russian poetry and the development of new poetic forms capable of reflecting these trends.

The era of unpredictable changes in Russia is generating new literary styles and new voices. With the growing crisis of personal communication and the apparent collapse of many ideological dogmas in Russian society, many poets are looking for new poetic tools to reflect on this new reality. In the second decade of the 21st century, a large group of talented poets writing in free verse has emerged at the forefront of Russian poetry. Among them are both established poets and poets of the younger generation. Alla Gorbunova, Andrei Sen-Senkov, Sergei Zavyalov, Nikita Sungarev, Nikita Safonov, Kirill Korchagin, Stanislav Lvovsky, Oleg Paschenko, Danila Davydov, Oksana Vasyakina, Igor Vishnevetsky, and many others have used the possibilities of free verse to create brilliant poetic texts outside the traditional content and metrical system of Russian lyric poetry.

At a time when linear self-expression is in crisis, a new trend is emerging: the expansion of non-lyric poetry. Free verse occupies an important niche in this process. According to the poet Fyodor Svarovsky, this is due to the fact that “traditional stylistics today is simply not suitable for many forms of poetic expression” (Svarovsky). This tendency follows the general logic of the development of Russian postmodern culture and its collision with obsolete structures. In poetry, it often takes the form of a lexical or syntactic deviation of the language. The contemporary development of the free verse in Russian poetry is consistent with the Western model of free verse, which allows the poet to narrate a poetic reality without a clearly organized structure or a pronounced lyrical attitude. This style is prevalent in Anglophone poetry today, and many contemporary poets are exploring the possibilities of free verse. For example, the American poet -laureate Austin Smith writes in the poem “The Hotel” (2011):

……the room

itself is simple

the sort rented out

night by night

to the poor to make

more poor or to die in

but it is not night

nor is she poor. She

could have afforded

a nicer room and it is

day

This almost documentary statement is full of drama and demonstrates an important aspect of free verse – its ability to express psychological momentum without any lyrical undertone. Its content is dense and aimed at the reader’s imagination. The same pattern of verbal communication or conversation on a “hot topic” can be observed in many works of modern Russian poets. Unresolved problems of the past, as well as current issues of social movements, injustice, and oppression, come to the fore as an example of civic self-expression and are popular with poets writing in free verse. Take, for example, Nikita Sungatov’s poem “What Have We Done to You?” (В чём мы провинились перед вами? (2015); its first verse consists of a direct appeal to the reader. It’s an invitation to dialogue on one of the most dramatic themes in contemporary Russian history and culture:

В чём мы провинились перед вами?

За что вы ненавидите нас?

Зачем вы воюете с нами?

Противопоставляете себя нам,

высмеивая и оскорбляя наши ценности.

What have we done to you?

Why do you hate us?

Why are you at war with us?

You are confronting us,

mocking and insulting our values.

The beginning of Igor Vishnevetskii’s poem “CAPSA” (Vishnevetskii 64) is reminiscent of a casual conversation:

Мы приехали туда поздним вечером –

у меня чудом сохранилось расписание поездов –

в 21.34. Огромное многозвёздное синее небо

накрывало Сахару шатром. В чайных работали телевизоры:

шёл чемпионат Франции и здесь, на дальних выселках

сначала римского, а после и галльского мира

все обсуждали марсельцев, прозевавших дурацкий гол.

We arrived there late in the evening –

I miraculously kept to the train schedule –

at 9:34 p.m. A huge, starry blue sky

loomed over the Sahara like a tent. TVs were on in the tea rooms:

the championship game with France was on and there, in the outskirts of the Roman world at first, and then the Gallic world

everyone was discussing the Marseilles, who had missed a foul goal.

Sometimes free verse is just a polyphony of thoughts and observations, as is seen in the striking short poem by Vasily Borodin “The Banner will Flutter” (Stiag zavyotsia 2011):

стяг завьётся сор взовьется свет ворвётся сердце взорвётся

время порвётся

всё остаётся

the banner will flutter the dust will rise the light will burst

the heart will explode

time will break

everything will remain

Fantasy, dry humor, or satire often testify to the poet’s detachment from difficult experiences, an inability or unwillingness to accept the realities of an ever-changing world. Published in Nikita Sungatov’s book The Debut Book of the Young Poet (Debyutnaya kniga molodoga poeta, 2015), a poem about the creative process of poetry, “There is a Method” (“Est takoi sposob” 2015), simultaneously reveals the experience of a young man in a modern urban environment:

Я хочу рассказать о том, как однажды

я принёс себя в жертву идеологии.

И о том, как, прогуливаясь по центру столицы,

вдруг обнаружил, что моё зрение

подчиняясь определённой логике

выхватывает из окружающей среды

некоторые детали

кажущиеся незначительными со стороны

I want to tell you about the time

I sacrificed myself to ideology.

And how while walking through the center of the capital

I suddenly discovered that my vision

followed a certain logic

it picked up

certain details that seem insignificant from the outside

An important feature of free verse is that the abandonment of the traditional pattern of meter and rhyme and structured form frees the poet in his quest to format the sound of the stanza as a whole. The ability of free verse to create new and unique prosody appeals to the reader’s perception rather than to syllabic meaning. In this case, the unity of non-metrical verse is preserved by the rhythm hidden in the sounding word, by a complex system of changing rhythm and intonation, which the reader perceives as the music of poetry. Free verse allows the author to encode many meanings and images in the short space of the stanza and which can still be perceived as a poetic utterance. The linguistic experiments of contemporary Russian authors often contain semantic deviation and metonymy: they allow a combination of both figurative and sound patterns.

One of the experimental poems by Lada Chizhova “Color. Practice” (Tsvet. Praktika) opens with the image of the “snowed-in city” but then moves the reader into different dimensions full of emotions and bewilderment:

город выбелило

в белила вляпаться всеми конечностями

и лицом

жжется

как смириться с телом готовым перемещаться

и расти

the snowed-in city is whitened

as if all limbs were plunged into white paint

and the face

it burns

and how to reconcile with a body ready to move

and grow up

Whether the nature of this kind of prosody represents a “repetitive metrical” or “irregular accent” topology (Manin 581-582) is up to interpretation. However, one of the important aspects of the modern free verse form is that it gives the poet the freedom to experiment with the word as the basic element of poetic speech and create an unpredictable pattern of changing rhythm. It also allows the poet to use different language registers within a single poetic stanza.

In addition to sound, poets sometimes use visual effects, such as the interruption of lines and the empty space between lines. This expands the space of the poem, as is seen in Sergei Zavyalov’s poem “Autumn. Peterhof” (Osen’. Petergof; 1994):

Кто-то скажет тебе

что это только засохшей листвы под твоими ногами

шуршанье

someone will tell you

that it’s only the rustle of dried leaves under

your feet

After all, the discussion about the nature and future direction of contemporary Russian free verse is still in its early stages. Gennady Aygi, the once unrecognized genius Chuvashian poet, called poetry a universal tool of world consciousness, which cannot be defined only by the traditional strict syllabic-tonic prosody. The Russian poetic scene includes the vers libre as an essential part of the postmodern literary landscape.

A жасмин надвигается:

словно душа – отодвинувшаяся

сразу – легко – от греха! …

Jasmine is emerging:

like a soul –

having pushed aside instantly

easily – the sin! …

– Aygi, 1969

Elena Dimov

Works Cited

Aygi, Gennady. “Poiavlenie Zhasmina.” Pamiati Muziki. Shubaskar, Russika – Lik Chivashii, 1969, p.6.

Borodin, Vasily. “Stiag zaviyotsia.” P.S. Moskva, Gorod-Zhiraf. Stikhi, 2005-2011. N.Y.: Evdokiia, 2011, p. 29. <https://brownianmotionfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/gorod-ghiraf_final1.pdf>

Chizhova, Lada. “Zaneslo gorod vybelil,” Tsvet: Praktika. Tsykl stihotvorenii, 2013. < www.litkarta.ru/studio/participants/chizhova-l>

Eliot, Thomas S.”Reflections on Vers Libre.” The text of “Reflections on Vers Libre” by T.S.Eliot. <https://www.theworld.com/~raparker/exploring/tseliot/works/essays/reflections_on_vers_libre.html>

Manin, Dmitrii Y. “Chopped-up Prose or Liberated Verse? An Experimental Study of Russian Vers Libre.” Modern Philology, vol. 108, no. 4, 2011, pp. 580–596 <https://doi.org/10.1086/660697>

Orlitskaiia, Anna. “Posleslovie.” Sovremennyi Russkii Svobodnyi Stikh: Antologiia Po Materialam Festivalei Svobodnogo Stikha (Moskva, Sankt-Peterburg, Nizhnii Novgorod, Tverʹ S 1990 Po 2018 G.). Edited by Orlitskaia Anna and Orllitskii, Iu. Moskva: 2019. vol. 2, p. 223. <https://rusfreeverse.com/books>

Svarovsky, Feodor. “O razrushitelnoi sile verlibra.” Novosti literatury, 10.06.2011. <https://novostiliteratury.ru/2011/10/novosti/koloka-avtora-fedor-svarovskij>

Smith, Austin. “The Hotel.” The New Yorker, Sept. 17th, 2012. < newyorker.com/magazine/2012/09/17/the-hotel>

Sungatov, Nikita. “V chem ny provinilis pered vami?” Debi︠u︡tnai︠a︡ kniga molodogo poėta. M.: Translit, 2015.

______________. “Est’ takoi sposob.” Debutnaya kniga molodogo poeta.

Vishnevetskii, Igor. “CAPSA.” Sovremennyi Russkii Svobodnyi Stikh: Antologiia Po Materialam Festivalei Svobodnogo Stikha, vol. 1, p. 64.

Zavylov, Sergei. “Osen’ Petergof.” Ody i epody. St. Petersburg: Borey-Art, 1994. <http://www.litru.ru/?book=45665&description=1>

Disclaimer

Translations of excerpts from works by contemporary Russian authors on this website are used under Fair Use solely for literary criticism and educational purposes.

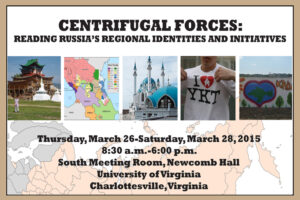

The proceedings of the UVa conference, “Centrifugal Forces: Reading Russia’s Regional Identities and Initiatives, ” March 26-28, will be broadcasted as a free online streaming event. Please find instructions to access the stream

The proceedings of the UVa conference, “Centrifugal Forces: Reading Russia’s Regional Identities and Initiatives, ” March 26-28, will be broadcasted as a free online streaming event. Please find instructions to access the stream