Drown Me, or Be Damned

Translated from the original Russian by Yuri Urbanovich and Michael Marsh-Soloway

Valentin Pikul (1928-1990) is almost forgotten author today. However, he was the most read author in the Soviet Union in 1970-90s. Although Pikul is not well known by Western audiences, his works sold over a million copies in Russian markets between 1967 and 1979. In addition to producing more than two-dozen novels, Pikul published hundreds of historical miniatures. This story, Drown Me, or Be Damned, describing the trials of John Paul Jones in the American Revolution and the Russian Imperial Navy, appeared in the 1988 anthology, Blood, Tears, and Laurels.

Pikul was born in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, but he grew up primarily in the small town of Molotovsk, now Severodvinsk, on the shores of the White Sea. At the outbreak of WWII, Pikul and his mother were visiting relatives in Leningrad. In the ensuing violence, they became trapped by the blockade of the city that lasted over 900 days. While residents of the city endured bombings, starvation, and brutal winters, Pikul and his mother managed to escape the siege by traversing the frozen surface of Lake Ladoga, popularly called ‘the road of life’.

Upon his return to the Russian North, Pikul enrolled in the Midshipman school in the Solovetsky Islands, and throughout the duration of the war, he served as a cadet on the minelayer vessel Grozny. During this time, he developed a strong connection to the sea, and an enduring fascination with naval history. After the war, Pikul became an author, and his writing flourished in a literary circle led by Vera Katlinsky. Shortly after his 32nd birthday, Pikul moved to Riga, where he produced most of his best works.

Pikul’s rich historical imagination resonated broadly with adolescent and adult readers alike, who enjoyed the author’s vicarious experience of pivotal scenes, events, and interactions from lesser-known annals of the past. In addition to providing audiences with the thrill of historical adventurism, Pikul’s texts promoted international collaboration through the presentation of common bonds uniting dissimilar nations and peoples.

In this regard, the figure of John Paul Jones serves not only as a heroic naval personage, but also as a personal bridge connecting the legacies of America and Russia. While John Paul Jones is most notably remembered as one of the founders of the American Navy, who fought vehemently against the British in the American Revolution, he also served with distinction as an Admiral of the Russian Imperial Navy in the Russo-Turkish War, and his efforts allowed Catherine II to proceed triumphantly through the annexed territory of Crimea with her ally Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II.

Despite looming hostilities of the Cold War, Pikul encouraged readers to reconsider bonds with people of different national and ethnic backgrounds. The popular reception of Pikul’s work demonstrates the resonance of themes promoting international collaboration, peaceful cultural exchange, and the ever-present possibility for rapprochement to settle the conflicts of divided peoples and institutions.

By Michael Marsh-Soloway

The American ambassador to France, Mr. Porter, studied the time-trampled cemeteries during his six years in Paris. In 1905, his research was finally crowned with success. In the Grange aux Belles cemetery, he discovered the grave of a man about whom several books had already been written, one by Fenimore Cooper, another by Alexandre Dumas.

“Are you sure you found Paul Jones?” – the ambassador asked.

“I’ll open the coffin and look at his face.”

“Do you think the Admiral has been well preserved?”

“Of course! The casket was filled to the top with embalming alcohol.”

It was unsealed, and after the strong grape spirit spurted out of the coffin, everyone was struck by the striking resemblance of the deceased’s face to the plaster mask of Paul Jones in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Two renowned anthropologists, Pagelion and Captain, examined the admiral’s remains very carefully and came to the conclusion:

“Yes, we have before us the notorious ‘master of the sea,’ Paul Jones, and there are even traces in his lungs of the pneumonia from which he suffered late in life.”

The body was placed into a metal coffin, on the cover of which was installed a small round porthole like that of a ship. A squadron of U.S. battleships set off for the shores of France across the Atlantic. In Annapolis, the Yankees were erecting a ceremonial crypt, so that Admiral Paul Jones would find his final resting place in America. Paris had not seen such an impressive procession for such a long time!

The coffin with the body of the sailor was escorted by French regiments and a cortège of American midshipmen. At the head of the funeral procession marched the Prime Minister of France, carrying a top hat in his hand. Orchestras played triumphant marches. Behind the gun carriage walked ambassadors and ministers from different countries in ceremonial style.

The Russian naval attaché mentioned with a smile to the Ambassador A. I. Nelidov: “The Americans firmly remembered that Paul Jones was the founder of the U.S. navy, but they have forgotten that the Admiral earned his rank not from America, but from Russia… After all, from us!”

The son of Scottish gardener, Paul Jones began his life like many other poor boys in England, as a sea cadet. He got to know the taste of the sea on a slave ship traveling from Africa to the American colonies. He learned how to predict danger in the darkness and the fog, but his soul was outraged by the cruelty of his countrymen. The young sailor left the slave traders’ ship, swearing to himself never again to serve the British crown.

“British ships deserve only to be sunk like rabid dogs!” shouted Jones in a seaport tavern…

The new world hosted the fugitive. In 1775, the American War for Independence had begun, and Lieutenant Paul Jones offered his service to a country that was not yet even printed on the world map.

Washington declared, “I recognize the spirit of this man…Let him fight!”

Jones gathered a crew of ruthless daredevils, who knew neither their fathers, nor their mothers, and who grew up without roofs overhead. With these men, he crushed the English on the sea in such a manner that sparks were flying from the haughty bravery of this ‘Master of the Sea’. They boarded ships in brutal battles, decided by the strike of a saber or a spear. Jones captured British ships, and tugged the dishonored vessels to American harbors, where now ashore he was gloriously honored by clamoring crowds of people…

Paul Jones turned to Washington and stammered, “And now I want to burn the skin of the English king in his English sheepfold. I swear to the devil, it will be so!”

In the spring of 1778, a seemingly peaceful commercial vessel appeared on English shores. In reality, however, the ship had 18 canons hidden beneath its hull. It was the corvette, “Ranger”, masked as a merchant ship.

“What’s new in the world, friend?” the sailors asked the harbor pilot when he boarded the deck of the corvette.

“They say,” he turned to the captain, “that close to our shores roams the traitor Paul Jones, and he is such son of a bitch, such a swine, that sooner or later he will be hanged!”

“How can it be so? You Englishmen have such a good opinion of me. Allow me to introduce myself: it is I, Paul Jones! But I am not going to hang you…”

In a thunder of grapeshot and hand grenades, while encouraging sailors with whistle and song, Paul Jones drowned British ships at their own shores. The London Exchange was experiencing a fever. The prices for all goods grew steadily, and bank officers declared bankruptcy as cargo ships sat idly in the harbors.

The pilot of the corvette pointed into the distance, where the city lights were flickering, responding, “There is Whitehaven, as you wished, sir. What are you planning to do here?”

“This is my homeland,” answered Paul Jones, “and one’s homeland sometimes needs to be visited even by a prodigal son, such as I!”

Showered by a warm nighttime mist, the sailors, led by their captain, descended into the city, seizing the fort, destroying all of its cannons, and after having burned down the British ships anchored in the harbor, again disappeared into the endless expanse of the sea…

The King, who was dispirited, lamented, “I am ashamed. Is the glory of my fleet merely myth?”

“What is to be done?” replied the admirals to the King. “Jones is uncatchable, like an old hull rat. There is no rope in your majesty’s navy, which wouldn’t generate bloody tears from the desire to strangle this impudent pirate on a mast!”

By then, Paul Jones had already descended into County Selkirk. In the castle, he encountered only a duchess, to whom he expressed his deepest apologies for the disturbance. Meanwhile the men from The Ranger were dragging all of the duchess’ silverware to the boat. In taking his leave from the fair gentlewoman, Jones personally obliged himself, until the end of his days, to repay the Selkirks out of his own pocket.

“But I am not such a robber as the English think me to be,” stammered Paul Jones. “If my glorious men have such a desire to have supper only on silver, then let them eat like nobility! They have so few joys in their lives!”

Soon after having rested with his crew in France, he again appeared in English waters aboard The Bonhomme Richard. This time he was accompanied by French ships under the banner of someone named Landais, who had been discharged from the fleet for insanity. Jones recruited him into his own service.

“I myself, when I fight,” Jones affirmed, “lose all sense of self. So this crazy man fits in perfectly with the matters that we are going to undertake…”

On the traverse of the Flamborough Peninsula, Jones saw through the fog, the high riggings of the fifty-canon ship of the line, The Serapis, which by its right was considered the best ship of the Royal Fleet, and behind it, the wind propelled the astonishing frigate, The Duchess of Scorborough.

At first, the Englishmen called to them on a bullhorn, “Identify your vessel or we will drown you!”

Paul Jones in a clean white shirt, rolled up his sleeves to his elbows, and answered with unusual rage:

“Drown me, or be damned!”

In this risky moment, ‘crazy’ Landais dashed behind the commercial vessels. Thanks to Landais’ obvious foolishness, the small Bonhomme Richard, squared off one-on-one with the thunderous royal opponent. The first artillery shot of the British rang out, and the American ship started leaking and burning. Throughout the volley, several cannons blew up during the first moments of the fight. The ships pounded with such fury for one hour, then another, then three, and the battle came to a close under the moonlight. While tacking sharply, and as showering sparks streamed down from burning sails, the enemies came so close to each other that the mizzen-mast of The Serapis suddenly crashed down before Jones’ feet, and he seized it with his own embrace.

“I swear,” shouted Paul Jones enraged, “I will not let go of the mast until one of us sinks to the bottom of the sea!”

The deck became slippery with blood. The Bonhomme Richard continued to fight in the crackling fires, losing cannons, masts, and spars. In the flames, one could hear whistling, obscenity, and song. The wounded Paul Jones continued to inspire his crew.

“Get ready to board the ship! Board the ship!” somebody screamed from aboard the Serapis.

“You are welcome!” Jones beckoned. “We will teach you a lesson that you will never forget!”

The English soldiers flew overboard, slashing with sabers, however, the power of the royal artillery also did its bidding: The Bonhomme Richard was sinking into the abyss with an audible hiss. The sea was already flooding over its deck, and suddenly they heard from The Serapis:

“Ahoy, it looks like you are finished. If you are surrendering, then stop fighting, and behave like gentlemen!”

Paul Jones suddenly threw a hand grenade at the English, with the quick reply, “Why do you think so? We haven’t even begun to fight!”

“It’s time for you to finish this story.”

“I will finish this story so fast, that you, I swear by the devil, that you won’t even have time to pray.”

The Bonhomme Richard collided into the side of The Serapis with full force; boarding hooks flying high clenched the wooden sides, and the two warring ships grappled with one another. Hand-to-hand combat commenced, and in this moment from the sea approached the ‘crazy’ Landais with his ships. Without understanding who is friend or foe, he covered the fighting parties with hot grapeshot, which immediately knocked out half of the English, and also half of the Americans.

“Now, he’s really lost his mind!” Paul Jones exclaimed, bleeding from his wounds.

But at this juncture, the captain of The Serapis surrendered his sword to Paul Jones.

“I congratulate you, sire! I have lost this match…”

The Bonhomme Richard was lost in the abyss with grappling ropes ripping as it sank, releasing huge gurgling air bubbles from the hold. A tattered, star-studded American flag was raised over the mast of The Serapis.

“And we are again on deck, men!” declared Jones to his crew. “We will board The Countess of Scarborough, and take it too!”

The victors headed for French shores on the two captured vessels. The burial rites of the fallen were read, the wounds were mended, barrels of wine were opened, canisters of “Yankee hash” were boiled, and the men cavorted and sang:

Cast a line in Puerto Rico, The cannibal waits onshore, Hum diddly hum!

Pray for our patron, dear Father, And we from our cannons, strike square between the eyes, Ah- ha- ha- ha!

The fight is now over, tonight we feast, And then we’ll sleep soundly, Hum diddly hum!

Everyone gets a piece to taste thigh, rump, breast, stomach, We clean the boiler down to the bottom, Ah- ha- ha- ha!

This spirit of rough times in this sailor shanty of antiquity was born in the stuffy taverns of the New World.

Flexible and dark, he looked entirely not like a Scot, but a Native-American Indian Chief. The look of his gloomy eyes pierced right through his interlocutor. His cheeks drilled in by the winds from all latitudes, were almost brown, like dates, and summoned to mind tropical countries. This is the extremely proud young face of friendliness that breathed contemptuous reticence. So this how his contemporaries remembered John Paul Jones.

Poets in Paris composed verses in his honor, but he did not like to be indebted, so he immediately paid for them with compositions of pleasant lyrical elegies. Parisian beauties started fashioning their hair in the image of sails and riggings in honor of the victory of The Bonhomme Richard. France, hostile to England from olden times, showered Jones with unprecedented favors. The King of France appointed him a knight of the crown, and in the Parisian opera, the sailor was publicly crowned with a wreath of laurels. The most distinguished ladies sought momentary interactions with him, and they displayed kindness in kind with a torrent of love letters.

Jones justifiably expected that the Congress of the country, for which he did so much, would appoint him to the rank of Admiral. He was outraged, when across the ocean, only a bronze medal was forged in honor of his exploits. Around the name of Paul Jones, which thundered across all the seas and all the oceans, had already begun the intrigues of politicians. Congress was jealous of his glory, and Paul Jones felt betrayed.

“I agree to shed blood for the freedom of mankind, but I do not wish to sink the burning ship for the gratification of shopkeeper-congressmen. Let Americans forget what I was, what I am, and what I will be!”

. . .

In distant snow covered St. Petersburg, the public had long followed Jones’ exploits. Catherine II, an experienced and cunning politician, immediately understood that beyond the ocean, a great country with an energetic people was now being born. She declared “armed neutrality” in support of America to win its freedom. Meanwhile, on the steppes of the Black Sea, brewed a new war with Turkey, and Russia always needed brave young captains for its fleet.

“Ivan Andreich,” Catherine II bid to the Vice Chancellor Osterman, “It would behoove us to entice the boisterous John Paul Jones into our service, so I ask you to submit a request through our ambassadors.”

Jones granted his consent to enter the Russian service. In April of 1788, Paul Jones enlisted and was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral as indicated on his Russian documents.

“The Empress received me with the most flattering attention that adequately affords a foreigner,” he told his friends in Paris.

The Russian capital opened the doors of its estates and palaces. Jones was showered with invitations to dinners and luncheons for intimate receptions in the Winter Palace. The British merchants, as a sign of protest, closed their stores in Petersburg. Hired British sailors, who served under the Russian flag, openly resigned. British intelligence sharpened its teeth and claws, waiting for the chance to ruin the career of Jones in Russia.

As a sailor next to the Russian throne, Jones conducted himself in Republican fashion. He boldly presented the texts of the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence as gifts to Catherine. The Empress, like a discerning woman answered him:

“I have a premonition that the American Revolution cannot fail to ignite other revolutions. The fire will spread!”

“Your Majesty, I venture to think that the principles of American freedom will open your many prisons, the keys of which we will drown in the ocean.”

. . .

The Rear Admiral left for the Black Sea, where he raised his flag on the mast of the Vladimir. He raised his own sailing squadron that smashed the Turks under Ochakov in the Dnieper Estuary. The brave buccaneer now performed in a different guise, consisting of dusty Cossack trousers with a curved saber at his hip. Paul Jones smoked Ukrainian shag tobacco from a pipe, and drank Cossack vodka, downing it with chuck jerky, garlic, and cucumbers. At night aboard the Zaporizhian sharp-nosed vessel, The Seagull, after ordering that all oars be wrapped, the Rear Admiral sailed lengthwise past the Turkish fleet. Aboard the flagship of the Sultan’s navy, Paul Jones etched his resolution with a piece of chalk:

Burn.

-Paul Jones

The Russians were delighted with his prowess, but he himself was delighted in the unparalleled courage of Russian soldiers and sailors. At the battle of the Kinburnsky Peninsula, Jones shook hands with Suvorov ‘like century-old friends’, as Suvorov described it, and the Turkish fleet suffered a terrible defeat. Paul Jones might have been an excellent seaman, but he was an incompetent diplomat, and his relationship with Prince Potemkin soon became detrimental to his standing. British intelligence, with an invisible eye watching Jones even in the Dnieper floodplains, waited for the moment to strike!

The blow was very painful, for it was during this period that James started petitioning for the development of trade between Russia and America. He made plans for the creation of united Russian-American squadrons, which were to be based in the Mediterranean Sea as a guarantee of universal peace in Europe, but with Prince Potemkin, he quarreled all at once.

The British rained down on him from St. Petersburg a torrent of lies and dirty rumors claiming he was guilty of smuggling, and that he shot his own nephew, and so on. There was no affair without bribery at the capital summit. Much is still not clear to historians, and due to the lack of documents, the corpus of legends based on lies of this time period only muddles the real picture. But historians discerned something in this all the same. Paul Jones was neither in the favor of the Russian navy, nor of the Empress herself. He never tired in ‘educating’ her of the constitutional spirit, touting the Republican way of life everywhere he went.

But after all, his resignation was submitted. Suvorov gave him a fur coat.

“In spite of it all, I will return to Russia,” Paul Jones said with conviction when the horses set off carrying the carriage to the gate.

After roaming around Europe like a homeless vagrant, he finished his run on seas and oceans in Paris.

Paris was different, having experienced revolution. The Keys of the Bastille were forwarded across the ocean as a gift to Washington, with the words: “The principles of America opened the Bastille!”

Henceforth, from Paris, the sailor set about his own project, the amazingly successful construction of a 54-cannon vessel, which the French hid beneath a broad cloth.

Catherine recognized features of Paul Jones in conversations with those close to her: “Paul Jones possessed a very quarrelsome wit, and was deservedly celebrated by despicable riffraff…”

This phrasing of the Empress is easy to decipher: “despicable riffraff” always surrounded Jones. There were always these people, craving freedom. They were his fellow Jacobins.

Then began a new phase of life.

From the window of his own squalid garret, The Мorraine Survey, he saw the tiled roofs of Paris and sweetly dreamed of powerful squadrons setting off into the ocean for the battle against tyranny.

. . .

Like all progressive people of Paris in his time, Paul Jones joined the Masonic Lodge of the Nine Sisters, which absorbed the best minds of France. In those years, he was surrounded by poets, philosophers, and revolutionaries, and he carried on the tutelage of his sincere friend Mrs. Telisen, the natural daughter of Louis XV. France wished for Paul Jones to head the revolutionary Navy, but the “surveyor of the seas” was already sick. Yes, he was sick and impoverished. He already carried on with a walking stick in his hands, but the white shirt of the sailor looked then, as it did on the eve of a battle, consistently waving, flashing dazzling purity.

Death struck him on July 18, 1792.

He died at night, all alone, when he was only 45 years of age.

He died standing up, leaning against as cupboard, holding in his hands an open volume of Voltaire’s works. A surprising end! Even in death, the admiral did not fall, and even death could not unclench his fingers firmly gripping the book.

The American Ambassador did not attend his funeral.

The French National Assembly dedicated the memory of a man who well served the cause of freedom with a moment of silence.

12 Parisian sans-culottes in the Phrygian red caps brought the foam of the seas to his grave. Then it was decided to move his body to the Pantheon of great men, but in the whirlwind of subsequent events, this all was somehow forgotten.

The place where Paul Jones was buried was also forgotten. In the end, most people forgot of Paul Jones…

But Napoleon thought of him on a dismal day in France, when Admiral Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.

“I am sorry,” Napoleon remarked, “that Paul Jones did not survive until our present days. Had he been at the head of my fleet, the shame of Trafalgar would never have befallen the head of the French nation.”

In 1905, the historian August Buél found a man in America, who preserved the memoirs of his great-grandfather, John Kilby, a sailor from Jones’ command of the Bonhomme Richard.

This Kilby wrote about Jones:

“Although the British proclaimed him the worst person in the world, I am obliged to comment that this kind of sailor and gentleman was unlike any I had ever seen before. Paul was brave in battle, kind in his interactions among us simple sailors, and he fed us excellently, and in general, he behaved as he should. If he was not always given a salary, then it is not his fault. It is the fault of Congress!”

Paul Jones took his place in the American pantheon.

Recently, one of our country’s historians N.N. Bolkhovitinov offered the monograph describing the fate of Jones’s legacy:

Honor your war heroes, as best as you can. Every school pupil knows about Paul Jones, and texts about the valiant captain should be found alongside biographies of George Washington, Ben Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Initially, we were somewhat surprised to see Paul Jones in such brilliant surroundings, but ultimately we decided that Americans know best just whom should be honored most. We, generally speaking, least of all conceive of the details, which somehow diminish the merits of the famous admiral.

Upon reflection, we can say the latter. Of course, somewhere in the depths of Paul Jones’ soul, there has always been the adventurer with the manners of a typical pirate of the eighteenth century. Does it not link his fate to the struggle of American independence, if he had not become an admiral in the Russian Navy? Who knows? Perhaps, he would have slid into the usual business of piracy on the high seas, but if he had remained in this bloody arena, Paul Jones would have probably left our history, appearing instead on the most brilliant pages of sea brigandage.

But life writes itself according to the fate of this remarkable man, and Paul Jones will remain in the peoples’ history as an Admiral of the Russian Navy, as a national hero of America!

Biographies of the Editor and Translator

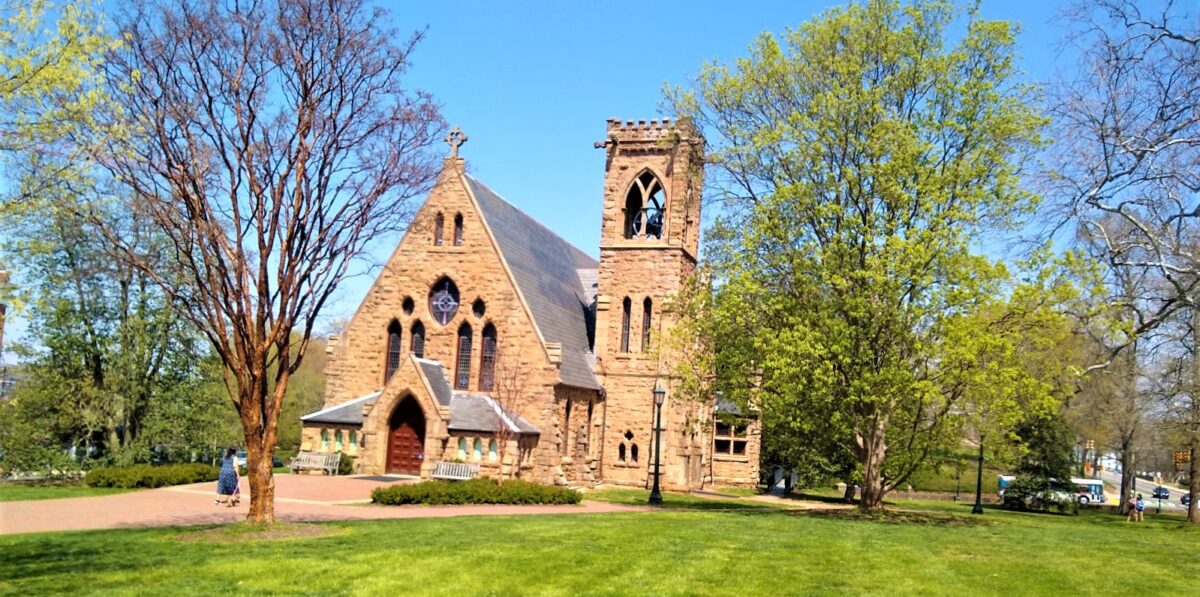

Professor Yuri Urbanovich was born in Tblisi, the capital city of the Republic of Georgia. He received his M.A. in International Relations from the Moscow State University of International Relations in 1972, and his Ph.D. in International Relations from the Diplomatic Academy of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1984. In 1992, Dr. Urbanovich was invited by the University of Virginia’s Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction (CSMHI) to coordinate dialogues defusing the “velvet divorce” between Baltic States and the Soviet Union. Currently, Dr. Urbanovich is teaching three seminars, Post-Soviet Challenges: National Ethnicities, Rise & Fall of the Soviet Union, and America through Russian Eyes.

Michael Marsh-Soloway is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Virginia. Throughout the spring of 2014, Michael embarked a tour of Moscow and St. Petersburg to conduct archival research for his ongoing dissertation project, The Ontological Necessity of All That is Imaginary: Mapping the Mathematical Consciousness of F.M. Dostoevsky. In 2011, he participated in the U.S. Department of State Critical Language Scholarship, and studied at Bashkir State Pedagogical University in Ufa, the capital of the Republic of Bashkortostan in the southwestern Urals. His research interests include the Russian novel, linguistics, and film.

**The editor and translator would like to express special thanks to Sergey Nikolaevich Dmitriev, Editor-In-Chief of Veche Publishers in Moscow for granting us special permission to publish the first rendering of this work in English. It is our sincere hope that the text will inspire interest among Western readers to investigate further the diverse writings and life experiences of Valentin Pikul.

Featured picture by Alexander Borisenko