Discussing ” new epic”

In an interview with “Vrij Nederlands” in 1982, in which he described Russian poetry, Joseph Brodsky mentioned that in his opinion there were only two outstanding poets left (Eugenii Rein and Yurii Kublanovsky – E.D.): “But whatever happens to Russia in the future, it will always have new literature, simply because of the Russian language. Russian is such a language that it’s impossible to stop the existence of literature in this language. Literature continues no matter what people do” (1).

Some thirty years later, in the situation of a prolonged crisis of individual lyric expression, we are indeed witnessing a remarkable new tendency in contemporary Russian literature: a growing interest in non-lyric poetry (non-linear expression), which critics have called a “revival of narrative poetry” or epic narrative. It occurred as an unexpected event beyond the limits of traditional poetic narrative and is related to the epochal shift within Russian society at the beginning of the 21st century. It is often described as a “new epic,” which has become a new literary phenomenon in 21st-century Russian literature (2).

What is a “new epic” and how is it different from an “old epic”?

One of the founders and creators of the term “new epic,” Feodor Svarovsky, assesses the current state of Russian poetry as an ongoing crisis of first-person lyric expression (or linear poetic reflection). In his view, the long line of Russian lyric poets that began in the Silver Age focused primarily on the inner world of their heroes. Svarovsky argues that this was simply not enough for modern literature and describes it as a crisis of traditional direct lyrical expression, which was also evident in European literature in general. This coincides with Ilya Kukulin’s opinion that “the poetic ego appears infantile and vulnerable and has lost all traces of the heroic” (3). Svarovsky points to a way out of this crisis: a new paradigm of poetic expression – narrative poetry without the author’s presence or emotional reflection. According to Svarovsky, “the author of the new epic does not narrate his own experiences, words, actions, and circumstances, but those of others” (4).

In his remarkable 2007 manifesto “New Epic,” Feodor Svarovsky declares: “I have long felt the impossibility of writing in the modernist paradigm of the 20th century, which was established by the writers of the Silver Age and then continued by the writers of the early-mid 20th century as direct lyrical expression… I don’t believe in a crisis of meaning…. It is simply that after secularization, after the crisis of humanism and the establishment of the postmodern approach to culture that took place in the 20th century, personal linear expression (by which I mean the author’s expression of the individual’s feelings, thoughts, and experiences) is no longer effective for achieving any significant aesthetic effect. .. What must be done to restore words to their former importance? I think we need to change the way the author expresses himself” (5). With this, Svarovsky suggests a shift in focus from the lyric hero to “whatever organizes existence outside of the author’s personal experience, feelings, etc. But what is that? The answer depends on the religious and philosophical views of the author and the reader. It could be fate, destiny, unknown forces, or even well- known forces that govern life.”

In his opinion, the difference between the “new epic” and the “old epic” is that the traditional epic narrative describes the heroic events of the extraordinary heroes that happened in the past and influenced life, which could be real events. But the “new epic” suggests that what lies behind all these events is always an unknown force, and it could happen anywhere (in space, in the past, in the future, in the imagination). The author’s goal is to provoke an emotional, aesthetic, intellectual contemplation “on these transcendental forces” by describing these events without interpretation.

Svetlana Gudkova describes several distinctive features of “new epic” works: the synthesis of prose and poetry for the sake of creating an exciting plot with many acting heroes whose fate depends on some transcendent power; the absence of the author’s presence or his narrative voice; the appearance of supernatural powers; the marginal and trivial heroes; the incorporation into the poetic text of many cultural symbols and clichés from traditional ballads, folklore, classical literature, and even the borrowing of plots from famous serials (6).

All this sounds like complete phantasmagoria, and indeed the new epic works are often rhymed long stories (poems or ballads) with a fascinating and constantly developing plot or series of bizarre events. The authors’ assumption that the poetic story, like life itself, is beyond the reader’s comprehension shifts the focus to more complicated, metaphysical processes. Readers can only guess at the nature of these processes, or at the forces behind the heroic actions of marginal heroes.

The “new epic” is flourishing and developing into one of the leading tendencies in Russian poetry.

According to Svarovsky and Rovinsky, a large group of contemporary Russian poets can be considered contributors to the “new epic” literary movement. Among them are Linor Goralik, Sergei Kruglov, Maria Stepanova, Andrei Rodionov, Arsenii Rovinsky, Boris Khersonsky, Pavel Goldin, and others (7). This group of undoubtedly talented writers is diverse and uses various poetic tools, from quasi-folklore to historical chronicles, to create exciting stories in verse.

This short essay introduces the works of two popular poets: Sergei Kruglov (Narodnie pesni) and Maria Stepanova (Proza Ivana Sidorova). Both poets are widely read in Russia and are attracting the great interest. They are very different from each other in terms of their poetic personalities and styles, but their poetry shows most of the characteristics of a “new epic” movement.

Sergei Kruglov is a rare combination: poet-priest. After graduating from Krasnoyarsk University, he worked as a reporter for the local newspaper in Siberia. In 1999, Kruglov was ordained a priest in the Russian Orthodox Church. His first Live Journal publications caught the public’s interest with their combination of great poetic talent and strong Orthodox spirituality. In 2008 he won the Andrei Bely Prize for The Mirror (Зеркальце, 2007) and The Typist (Переписчик, 2008). The echo of Orthodox Christian philosophical thought is evident in his work:

The smoke of prayers

Rising here and there over Russia!

Crawling, blending into a dark storm cloud,

They sprout lightning, they thunder, they howl fearsomely

Clash powerfully —

What a battle of prayers raging

Above the country! How it swirls,

No worse than the sparkling juicy battles of Uccello!

No, the Lord sighs bitterly, the analogy with a painting is inappropriate —

These are real people after all,

Here they squabble in such a non-picturesque fashion,

Pushing each other aside, trying to climb closer to Me,

Heads and hands seething

In the cauldron of this perpetually boiling country!

Excerpt from Nathan and the Elections of the Ruler.

Translated by Vitally Chernetsky (8).

What makes his narrative poems unusual is the ability to bring both the “tragic” and “beautiful co-existence of God and our neighbors” (ближние) into his poetic expression. Kruglov is well aware of his mission. In his hypostasis of a priest, Fr. Sergei is concerned with the “low, rejected, smoky, sore sky of/our life” flowing into “oblivion”. He believes that “transformation in lives is always the manifestation of the mercy of the Lord, incomprehensible to humans “(9). The poet Sergei Kruglov successfully brings his sacred knowledge to readers through vibrant polyphonic narrative.

Mirror

I am Your image, Lord, I am

Your little mirror.

Look at me:

These shadows under my eyes,

These wrinkles,

This bitterness, this hope.

Bring me to your lips, oh Lord,

Breathe on me:

Make them sure that You are alive.

Kruglov’s Folk Songs (Народные песни, 2010) are variations on traditional Russian folk stories and songs and introduce well known (for Russians) personages. Re-telling the folk stories in his own words, Kruglov masterfully incorporates motifs of Russian folklore in verses. One of them is Russian Fairy Tale (Русская Сkазка) – a quasi-folklore poem with classical Russian fairy-tale characters: Sirin-Bird (Птица Сирин), Nav-Morevna (Навь Моревна ( 10) etc.

Russian Fairy Tale

Russian Fairy Tale

Птицу Сирин в небесах молнией сразило,

Пала – и течёт

Мёдом лета позднего.

Костяные лики лет щелку отворили,

Смотрят: не пора ли? –

Цепи ржавы, гроб хрустальный

Грянется, расколется,

Кровью вытечет на дно

Голубое наше злато, дымное, берёзовое! –

Милая, не плачь, не бойся –

Костяная навь морочит,

В чёрных гранях душной ночи

Среди туч – забыта книга,

Колокольный звон берёз

Осень-Волхв пояла, скрыла

В кладях памяти, в пещерах, в тридесятых тронных залах, –

Слышишь хохот?

Навь-Моревна торжествует, яблоки роняет сад!..

Спи, не бойся, доченька!

Помнишь, как там в сказке дальше:

«Жила-была мертвая царевна…» –

Дождь стихает, гроб висит,

Август-Зеркальце разбилось: нет

На свете краше, выше, глубже, постоянней,

Нет страшней и безысходней, слёзней, обречённей

Этой ночи в августе,

Этих мест и этой речи,

Страшно мёртвой вживе, сказочной, последней, –

Спи. Выходят семеро,

На руках несут царевну; плывет месяц-кладенец;

Серебро течёт и тает; небо любит нас;

Спи, моя хорошая.

1994 (11)

Sirin-bird was struck by lightning in the skies

She fell down and flowed

Like late summer honey.

The bony faces of years opened a crack

looked: was it their time?

Rusty chains, a crystal coffin

would clap and crack,

they would flow to the bottom like blood.

Our gold is blue, it’s smoky birch!

Dear, do not cry, and do not worry.

In the black edges of sweltering nights

evil spirits would fool us.

On a wooden terrace in a garden washed

by rain under the clouds

a book was left forgotten.

Birches were ringing as bells.

Fall-Magus sang, and hid

in its memory’s treasures as in a cave.

Do you hear the laughter? –

It’s in a far away kingdom’s chambers

Nav-Morevna triumphs.

The garden drops its apples!

Sleep, fear not, my little daughter!

Remember how the story continues:

“There once was a dead princess…” –

The rain subsides, the coffin hangs

August-Mirror shatters – there is

no other night in the world more beautiful, higher, deeper, permanent

terrible, hopeless, tearful, or doomed

than this August night,

than this place and these words.

The frightening and marvelous dead is now alive

Go to sleep. Seven come out,

in their arms they carry the princess.

Silver flows and melts; heaven loves us.

Sleep, my darling.

Tr. by Elena Dimov

Phantasmagoria in a Russian Provincial City

Maria Stepanova is a prominent writer and editor of the website Colta.ru. Her acclaimed The Prose of Ivan Sidorov contains the activity of forces that bear resemblance to Bulgakov’s devilry. In 2007, Stepanova published The Prose of Ivan Sidorov (Проза Ивана Сидорова) on her blog in “Live Journal” under the name Ivan Sidorov – hence the title (12). It immediately caused a stir among Russian critics and readers. Her poem became a hit and was performed in a theater in November 2007. It was published a year later and has since become a representative example of “new epic” poetry. Its title “Prose” indicates that it is a story in verses, or a synthesis of prose and poetic text. Mark Lipovetsky calls it a “verse narrative” (13) and describes it as a “roundelay” (хоровод) of a modern phantasmagoria. Ghoul-criminals, the Black Hen from Pogorelsky’s story “The Tale of the Black Hen” and Bulgakov’s motifs, as well as a mystic-cop series merge into “a muddy lump”(14) in a story whose undertone is the agonizing guilt of the main character, Aleosha.

So what is it about this story that grabs the reader’s attention? At first, the story is too incredible to be taken seriously. In a small provincial town somewhere in Russia, the phantasmagoria begins one winter night when a half-drunk man enters the train station. The quiet, dreamy life of a provincial town is suddenly transformed when the main hero, the marginal Aleosha, arrives. The reader doesn’t know anything about his previous life, but it’s clear that some traumatic experience has brought him here:

In the provincial town, so to speak,

but in a low-minded way

with white steep cliffs,

with on-shore over the giant strides,

with the tubes of heavy industry,

with women, similar to the touch

like bottles with tight tops, arrives a drunken man.

The city, say, under the Snowy Shroud. The lights are off.

Carefully-painted, fences are dark, and even in the square there are no cops.

The adventures start when the drunken Aleosha finds a sleeping girl and the black hen in a waiting room, and brings them to a small hut:

In a waiting room a screaming hen runs across.

In the glass doors emerges a night patrol.

A sleeping girl – below the steering medium-sized adult bike –

and where is her mother? and who is she, trash?

A Hero, a Black Hen and a Sleeping Girl

As the poem progresses, Aleosha becomes the center of bizarre events involving a gang of supernatural criminals and the police. The following events describe the violent clashes between the supernatural criminal powers, led by the Black Hen, and the Moscow police forces (МУР). The modern setting is suddenly interrupted by forces beyond the comprehension of the heroes or the readers. The characters become mere elements in unpredictable processes, real or imaginary, and the narrative moves into a metaphysical space. Aleosha is by no means a true hero: when police forces arrive at the small house to arrest a gang of supernatural criminals under the leadership of the Black Hen, all the inhabitants are hiding under the bed. By the will of an unnamed power, Aleosha turns into a rooster, but he bravely protects the Black Hen in prison. All the heroes are saved in the end, but during the party of the supernatural gang with their leader, the Black Hen, there is the appearance of the beautiful Major Kantariya from the Moscow police force, who is looking for her lost daughter:

Rocking on black, smartly styled heels,

a beauty comes out of the shadows, with a gun in her hands,

and holding two targets in one sight,

she says: “Whoa, gangsters!

I am Major Kantariya from the Moscow MUR,

it’s done, and I reached my goal.

Hands behind your back, stay facing the wall.

I have a special price for your lives,

but I will end them

if those who are here

will not return my daughter to me here and now!”

At the end, Aleosha was saved from evil spirits and had a final chance to talk to his dead wife, who was incarnated as the Black Hen. Their conversation gives a final closure for Aleosha’s guilt and grief. The Black Hen then ascends to heaven, leaving Aleosha on this earth to proceed with his life.

The synopsis of this story reveals a modern ballad (it was even compared to a popular TV series “Место встречи изменить нельзя “). But behind the post-modernist absurdity is a story about lost love and guilt, as well as about all conquering mother’s love for her child. The tragic person of Major Kantariya in a search of lost child became one unforgettable symbol in the poem:

They left in a hurry like this: in front there was

a beauty with her daughter pressed to her chest,

and wrapped in a warm cloth.

Behind them left an angry man,

and the hen looked away from the basket

like a nail, not packed to the cap.

They walked on the white and then through the blue,

and from the hill they looked back, like a single soul:

at inanimate policemen near an abandoned house,

standing in the winter dusk,

without breathing in the snow dust.

The transformation of the Black Hen into Aleosha’s dead wife, her plea to supernatural forces to return the girl to Kantariya, the tragic and magnificent monologue of the “invisible power” at the end of the poem completely change our perception of the poem. We understand that at this moment the girl is brought back from another world by her mother’s love. Stepanova synthesizes timeless emotions and ideas of human destiny with symbols of pop culture and modern folklore. By appealing to the reader’s imagination and using recognizable cultural symbols and the environment of the Russian provincial town, Stepanova succeeds in creating a modern epic story about the eternal search for happiness and forgiveness. As it was a hundred years ago, provincial Russia remains a place where the idea of humanity grows out of chaos and despair.

References

- Brodsky, Yosif. Bol’shya kniga interv’yu. M.: Zakharov, 2000, p.199.

- Svarovsky, Feodor. “Neskol’ko slov o novom epose”. Zhurnal RETS: Novyi epos, 44 (June 2007). www.polutona,ru/rets/rets44.pdf

- Kukulin, Ilya. “Aktual’nyi russkii poet kak voskresshie Alyonuoshka i Ivanushka.” Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 2002, N. 53, p. 275.

- Svarovsky, Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gudkova, Svetlana. “New Tendencies in Contemporary Poetry: Artistic Species of M. Stepanova’s Book The Prose of Ivan Sidorov .” Izvestiia Rossiiskogo Gosudarstvennogo Pedagogicheskogo Universiteta im. Gertsena, 2009, N. 118, pp.12-15. cyberleninka.ru/article/n/o-novyh-tendentsiyah-v-sovremennoy- poezii-k-voprosu-o-hudozhestvennoy-spetsifike-knigi-m- stepanovoy-proza-ivana-sidorova

- Svarovsky, ibid.

- Kruglov, Sergei. Tr. by Vitaly Chernetsky. Jacket 36, a free internet literary magazine, 2008. jacketmagazine.com/36/rus-kruglov-trb-chernetsky.shtml

- Viazmitinova, l. ” Ipostasi Sergeia Kruglova”. NLO, 2011, N.110. litkarta.ru/dossier/o-knige-devushki-pojut/dossier_4278/view_print/

- Навь Моревна ( or прекрасная Марья Моревна – пленница Кащея ) is one of the most ancient and mythic goddesses in traditional Slavic beliefs. Sometimes she is a pagan-goddess in the image of tall woman with long hair, sometimes a beautiful girl in white. She is not only a nightmare from the palace of Kaschei, but the personification of fate, responsible for changes in human lives.

- Kruglov, Sergei. Narodnye pesni. M.: Zentr sovremennoi literatury, 2010, 116p. polutona.ru/printer.php3?address=0508112515

- Stepanova, Maria. Proza Ivana Sidorova. M., 2008, 74p. vavilon.ru/texts/stepanova6.html

- Lipovetsky, Mark. “Roodina-zhut’: o “Proze Ivana Sidorova” Marii Stepanovoi”. NLO, 2008.n.89, pp.248-256.

- Ibid.

Disclaimer

Excerpts from poems and translations of contemporary authors are used under Fair Use for educational purposes only.

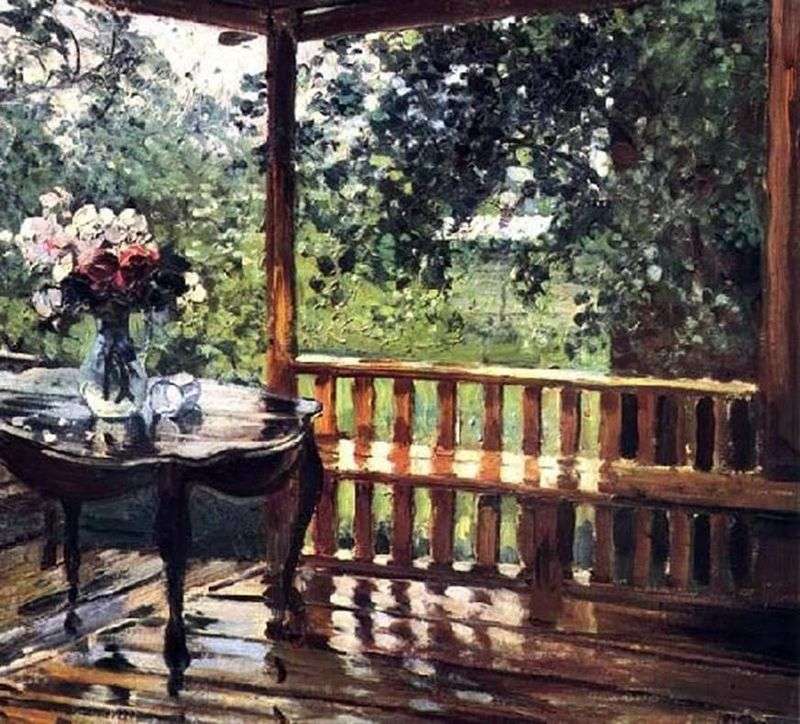

Picture “After the Rain” by Alexander Gerasimov, 1935.

We would like to thank Alexander Borisenko from Vladivostok, Russia for allowing us to use his photo on this website.