An Excerpt from Anna Grom and Her Ghost by Maria Rybakova translated by Elena Dimov

About the Author

Maria Rybakova was born in Moscow. She studied Greek and Latin in Russia, then in Germany, and subsequently in the USA. She currently resides in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Her first novel, Anna Grom and Her Ghost, was published in 1999 and translated into French and German. Rybakova is a recipient of numerous literary awards in Russia, including Students’ Booker Prize, Eureka Prize, the Russian Prize and others.

Maria Rybakova was born in Moscow. She studied Greek and Latin in Russia, then in Germany, and subsequently in the USA. She currently resides in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Her first novel, Anna Grom and Her Ghost, was published in 1999 and translated into French and German. Rybakova is a recipient of numerous literary awards in Russia, including Students’ Booker Prize, Eureka Prize, the Russian Prize and others.

About the translator

Elena Dimov was born in Vladivostok and grew up in the Russian Far East. She graduated from the Far Eastern Federal University with a master’s degree in Oriental Studies and Chinese Language. She holds a Ph.D. in Russian History and Culture from the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. After living in Europe, she now resides in Charlottesville, where she teaches Russian language and culture. Her primary scholarly interest is in contemporary Russian poetry.

Elena Dimov was born in Vladivostok and grew up in the Russian Far East. She graduated from the Far Eastern Federal University with a master’s degree in Oriental Studies and Chinese Language. She holds a Ph.D. in Russian History and Culture from the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. After living in Europe, she now resides in Charlottesville, where she teaches Russian language and culture. Her primary scholarly interest is in contemporary Russian poetry.

28th Day.

Dear Wilamowitz!

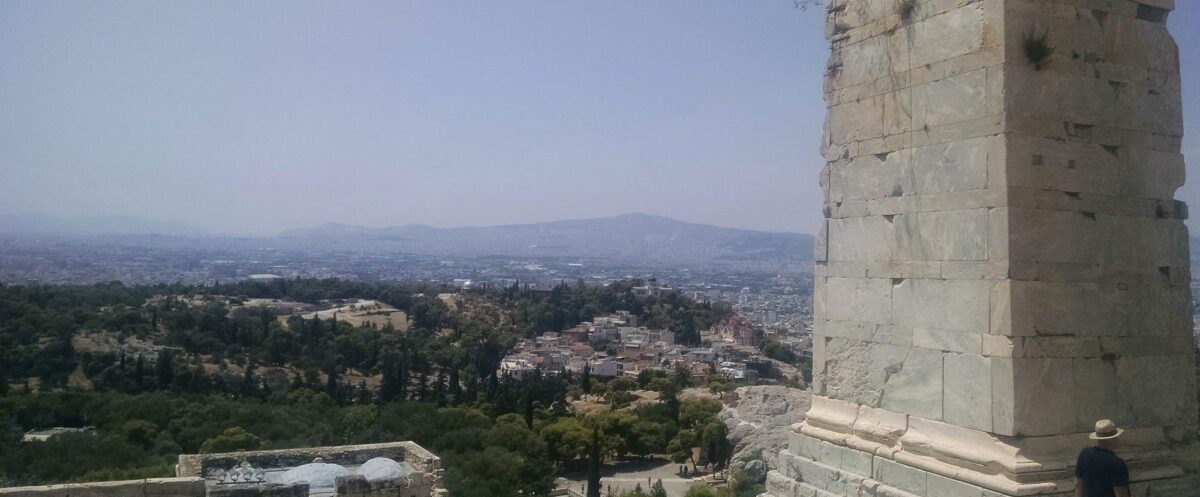

The bright light that some hope to see after death should not be sought in death. We, phantoms, wander in the twilight. The bright light should be sought where the land exposes its chest under the sea’s blows – in Greece. Myths like beacons are scattered in our souls like islands of this light. I came to this land of light, and it turned out that white columns did stand against the blue sky in reality. And because I couldn’t imagine anything more beautiful, I kept trying to touch them and I couldn’t believe that this beauty and my existence suddenly intersected in this moment. This scene, which I had imagined so often as a child, now seemed to have crept out of my most cherished dream, and it happened not because this dream arose by itself, but because it was derived from books. But in the course of time, especially when I had forgotten what I had read, the boundary between the written word and the imagination had worn away, and I had almost forgotten that this world and these columns did exist only in my mind. When I saw them in reality, I thought the world and I had swapped places and now the tourists were roaming the hills and gardens of my imagination.

The crowds of tourists bothered me. It was frustrating to see all these plebs in colored shorts with their cameras now walking in the places that were meant for the elite, for the elders, or for the priests, or just for the free-born citizens of Athens. Their unpleasant faces and flabby legs, their whole degenerative complexion, seemed to contradict the spirit of this place and violate the ancient ruins. After I met you, an idea of my exclusivity was born in me, and the statues of the gods and the ruins of the temples seemed to confirm this idea. I thought that it would be impossible to destroy the human hierarchy, just like it’s impossible to destroy these ruins that exist until our time, and even though they have turned to dust in reality, they still live on in our imagination. What was wealth? What was the meaning of success? After meeting you, I realized what the ancients meant by the word kalokagathiya. You were so much more perfect than the people around you that you seemed to be a representative of a different biological species that, by its very existence, disproved the idea that there couldn’t be a natural superiority of some human beings over others. You radiated superiority and exclusivity, and approaching you seemed like attaining immortality.

In dirty and muggy Athens I had to stay overnight in a strange hotel; it seemed that these are called rooms by the hour. It was on a central street leading to the Acropolis, but it was artfully hidden between relatively more respectable hotels. Previously it was apparently a brothel. Marble staircase and dusty velvet curtains adorning the foyer seemed remains of the past luxury. The ceilings were high, but the dirt seemed to accumulate even under the ceiling. The hotel was cheap and empty, if you didn’t count the old, drunk, and low-necked concierge and a woman I met who walked holding on to the walls. She filled the space under the high ceilings with the smell of alcohol. I wasn’t alone. I was accompanied by a relatively young German man who, having visited Greece before, had a strange peculiarity: he couldn’t stand the sight of the Acropolis. This peculiarity caused even more difficulties because the Acropolis could be seen from almost anywhere in Athens. So he had to walk with his eyes downcast, observing the piles of garbage in the streets and the stray cats.

The room we were given was large, but almost all the space was taken up by a bed covered with an unclean blanket full of holes. Lying on the bed, you could see yourself in the large broken mirror hanging on the opposite wall and wonder what circumstances had led to the mirror being broken. The furnishings were complemented by a sink with running cold water. I decided to take a shower, left the room, and went down a long dark corridor in anticipation of coming across some person standing unsteadily on his feet, but this time it was lifeless. The bathroom was located at the end of the corridor. The narrowness of the space and the height of the ceiling began to annoy me. There was no light in the bathroom, and when I locked the door I had to wash in the unreliable light coming in through the cracks in the door. It wasn’t a shower typical for hotels, but a spacious marble bath as dirty as an entire hotel itself. The water turned out to be cold, and it didn’t go through the hole but began to fill the bath with a murky fluid. I thought that it might be salty to taste, and at the thought of trying this slush I felt sick, gave up on the idea of taking a shower and returned to the room.

A bare bulb illuminated the dismal setting. I went out to the balcony – there was even something like a balcony where I could hardly even squeeze into – to smoke. This fortified my spirit. They make excellent cigarettes in Greece! The city noise gradually subsided, but this didn’t bring calm, as the Athenian streets begin rustle early at day break, and after a quiet Berlin to be awakened by this noise meant immediately to realize that you are being awakened in a foreign city. Yet, even Berlin was a strange city for me, and all other cities differ only in the degree of my being accustomed to them, otherwise all were alien. But the cigarette smoke wasn’t to be taken away; it was mine, because I sucked it into the very inside of my lungs and exhaled it into stuffy Athens, thereby providing a part of myself to it. Smoking is probably the only way to communicate with a foreign land. Puff – exhale, and your lungs expand to the size of the foreign country. And the tobacco smoke obscures its clear air.

The next day I went to the agora where once upon a time Demosthenes and Isocrates walked, but who could possibly believe it nowadays? Shopkeepers from the shops huddled near the Acropolis offered to let me come in the evening to smoke weed. And the elderly young man was following me like a shadow. Sometime in the early summer this young man had become the object of my short-living passion; it was then that this trip was planned, but after I met you the circumstances changed and there was no way to explain it to him. And I ran away from him.

At first I ran away just to eat alone. I went to a large open-air restaurant, exactly at the foot of the Acropolis. There was music playing. At the beginning, everything was peaceful. I ordered the swordfish and began to eat. A girl selling flowers scurried between the tables. Someone got up from a table and danced the Sirtaki. All in all, there was everything that the tourist’s soul desired. All of a sudden I felt someone’s glance. It was a grim bearded man sitting a few tables away from me. I looked away but after a few minutes decided to check again and looked up. Beardie continued to stare as if I were his acquaintance. After some thought, I came to the conclusion that no, we couldn’t possibly know each other. I looked up again, wondering whether to stick out my tongue at him, but his gaze embarrassed me and I decided it would be better just to stare at the plate. So I did, even if it spoiled my enjoyment. What was the point of sitting in the center of Athens, when all you could see was swordfish? After a while I felt someone approaching my table. I decided that the bearded guy had gone on the attack and shrank in horror in my chair. But it turned out to be the flower girl. She plopped a bouquet of nasty-smelling roses down on my table. I faltered, in broken Greek, saying that I don’t need roses. She said the roses are paid for, and pointed to the bearded man. The bearded guy nodded his head and perhaps winked to me behind his glasses, but I couldn’t see for sure. The salesgirl retreated, leaving me with a bunch of damned roses.

What could I do? Pay the bill and leave? But I didn’t know where to go and I certainly didn’t want to go back to the brothel. So I decided to outstay the bearded man. I ordered an ice cream and began to eat it in very small bits. I have always been proud of my ability to eat ice cream slowly, especially since I involuntarily eat everything else very quickly. I decided that I would think about something pleasant or important. But the bearded guy kept returning to my head. Because I didn’t have any information about him, my thoughts turned out to be almost meaningless, although intense. I thought: “bearded guy.” Sometimes I thought: “damn bearded guy.” And sometimes: “bearded guy, for hell’s sake.” But my thoughts didn’t extend beyond that.

And when for the twentieth time I thought “my god, bearded guy,” I looked up and noticed that he had disappeared. I outlasted him! This is what you can achieve with persistence. But I didn’t know then that restaurants, like the sea, conceal many sharp underwater rocks. At the table in front of me there was a pair of middle-aged people – the imposing gentleman and the small lady with plucked eyebrows. The lady was talking all the time, but the man was barely listening and looking around him. With foreboding apprehension, I noticed that his eyes met mine more and more often. But since he was with a lady, I decided that I wasn’t in danger.

But when I once again plunged a spoon into the ice cream to pick up a small, very small piece of ice cream, and then keep it on my tongue for a longer time, I saw the lady getting up and approaching me. She looked like she was going to hit me. But I reassured myself that she probably wanted to ask me for some matches. Of course she was going for the matches and I was about to get them out. But she didn’t need matches; she was interested in my nationality. She came up to me and asked in English: “Miss, what is your nationality?” Not being prepared for this sudden interrogation, I was confused and decided I should immediately admit it. “Jewish,” – I muttered. “Jewish? From Israel?” – She said in surprise. I was relieved. “No, I am from Russia… I am Russian, so to say…a Russian Jew…” I got confused in the subtleties of my national origin but she seemed to lose interest in this topic. “I am from France”, – she introduced herself, – and my friend is from Athens. If you want to spend the night with him, you can take him.”

And there it was. I remembered what my grandmother advised me to say in a sticky situation, and with dignity I said – “No, thank you. I have other plans for the evening.”

But she didn’t go away. “I don’t care about your plans”, – she said rather impolitely. “My plan was to spend this evening in the restaurant with my friend. This is our last evening. Tomorrow morning I am flying out. But he stares at you all the time, so if you want him for the night, take him.” Without waiting for my answer, the lady turned around and headed to the bathroom. Then her companion turned to me.“She is crazy, isn’t she, Miss?”- He said with a smile. – “And by the way, where are you from?”

I advised them to sort out their relationship without attracting strangers, paid off the bill and left. Then I took a cab to the railway station. Never before had my appeal reached such heights as this evening. In the taxi I anxiously looked askance at the driver, but my charms evidently had no effect on him. Upon arrival at the station, I studied the schedule, determined to catch the first train going to a more or less interesting direction. A train traveling to Corinth caught my eye. “I’m going to Corinth,” – I decided. The train’s wheels started to rattle and Athens went out of sight.

29th Day

Dear Wilamowitz!

Modern Corinth lies on the seashore and I had to take a bus to get to the ancient city, which is in the foothills. I stayed in a cheap roadside hotel. It was already night so I went straight to the first floor. When we recall our journeys, we usually remember the monuments or landscapes and forget the successions of rooms in which we stayed. That makes sense because rooms as a rule are all similar to each other. However, the small events that have happened to us in these rooms influence how we perceive the monuments for the sake of which we came. When I touched the column in Athens and thought that maybe Demosthenes had touched it too, the impossibility of it arose between my fingers and the column’s marble, because these twenty something years I brought with me to the agora, as well as the morning coffee I drank at the coffee shop, surrounded me like a thick wall. I remember that there, in a small room in Corinth, while I was taking a shower, my sandals got soaked and became completely ruined, so I had to throw them out when I left.

The room was square and there was an exit to the corresponding square roof of the ground floor. When I went to bed (I was very sleepy), I remembered that there are earthquakes in Corinth. It seems that someone told me that there was an earthquake in Corinth a few years ago. I almost got scared because given my adventures so far, it would be surprising if I were not overtaken by earthquake. But I was so tired that I fell asleep very quickly, and before the final plunge into insensibility I had time to think that contrary to my custom, I was falling asleep quickly.

Then something happened which I still don’t know whether it was a dream or reality. I woke up due to the fact that the room was rocking. I opened my eyes and saw that I had forgotten to turn off the lights, and the light bulb over my head, which was casting an uneven light, swung like a pendulum to the direction opposite from where it was suddenly thrown. In the moment following my awakening, the whole room had returned to its original position and I caught them on their way back: the bed, the wall, the light bulb cord – all had shifted and they no longer represented a series of parallel and perpendicular lines. In the same instant as the loss of balance there was a feeling of horror that engulfed me. But I didn’t have time to think about running and escaping from the room, because it ceased rocking, and then sleep overpowered my horror.

Upon waking up in the morning, I went through the balcony door to the flat roof of the ground floor. The sun was shining with a vengeance even though it was already the beginning of October. The air was transparent to the extent that you could see all around for many miles, way down to the sea. I saw gardens, which I wouldn’t pass through, houses, which I wouldn’t be able to visit, and I wanted to go everywhere right now so badly that it was almost painful; to see them and at the same time to know that it couldn’t happen. Even if I could go down there now and enter some of the gardens, it certainly would be different from what I’d have seen on the flat roof, and what I saw would be farther removed once I entered. But the air, which was translucent to the extent that it seemed that even the sunlight had a physical solidity, was so calm and motionless that I decided to consider everything that had happened that night a dream.

Then I went out to eat, get some rest, and to somehow pass the time until five, when I found out that there was also Acrocorinth, an ancient fortress on the mountaintop. I was told that from there you can see the two seas at the same time – the Saronic and the Corinthian Gulf. And I, having put on my sneakers, decided to climb up there. I went out to the road, where a sign was marked “To Acrocorinth” and began walking along it having decided it would lead me to the fortress. But it didn’t happen; the road didn’t rise steeply and smoothly but meandered around the hill, so when I looked up at what I thought had to be the fortress, it gradually turned out to be the opposite side. All of a sudden, I realized that the place from which I had come was by now far below. Since I wasn’t aware of the distance I had been walking for a long time, my ascent appeared to be almost sudden. For a time I trudged with my back forward, so that my glance wouldn’t be fixed on the upcoming goal but my eyes might freely scan down the mountain, taking in the whole panorama below me. Everything beneath me was mine. I understood that even after I descended from the hill, I would know, walking through those streets, that I had seen them from the top; and now, standing at the top, I imagined myself as a little figurine walking down one of those narrow ribbons which my eyes could still detect; and I realized that my gaze, by subordinating everything for many miles around, had power not only over what I saw but also over my own body. I had not been able to formulate the idea precisely, but while I was looking around the hills and imagined that I was walking down the road, I understood that there was something within me that was stronger and bigger than my surroundings, though at the same time it was stronger and bigger than myself.

I climbed this mountain as if there would never be another chance to climb somewhere else. Before, I often had dreams of a mountain in front of me, to which access was blocked; these dreams didn’t return after I ascended the serpentine road to Acrocorinth. On the contrary, after death I remembered everything, down to the smallest detail. But while I was climbing this mountain all my memories remained behind and were obliterated. Nothing else was left: there was no abandoned native country with its maze of five-story buildings, the washed out roads, the cruel childhood friends. There was no other country, where a foreigner is reduced to such obscurity that he strives to turn into a grasshopper. There were no pubs, no post offices; there were no more dirty windowpanes. There was no more of my awkward body, or the face that returned to me in the mirror every morning, after I lost it in the flexible spaces of sleep. There were no bad grades, no domestic quarrels, no rain, no contempt, or anything that darkens life and makes it look like death.

With every step onward, the sun shone brighter. I found myself without a past and realized that the past was death, and oblivion is life itself; and only you, without a past, without a future, you were the real one who supported me in my ascent and, it seemed to me that you were the only one who was waiting for me at the top. Fate, the blind guide to death, turned out to be weaker than you; its tenacious embrace unclenched, and I hurried to you so that you would accept me and never let me go.

When I finally reached the top, it began to get dark. I write “it began to get dark” out of our northern habit. Here in the south, there is almost no twilight. It’s weird, because the half-light semi-darkness of the north is similar to ourselves; and the southern darkness coming unexpectedly frightens us because it’s like sudden death. The serpentine path ended, and I had to climb over the rocks and watch my step; sometimes a rock slipped under my feet and began rolling down the slope. In those places which to me seemed impassable, a herd of sheep suddenly trotted through, their bells jingling in the darkness.

I found the point where you could indeed see the two seas at once; but I was guessing at the dark water only by the absence of lights: there was a glowing strip of land between two dark semi-circles, where by now the Greeks must be sitting in the coffee shops and discussing the news. “I see, I see the two seas at the same time!” – I said to myself (in fact, I only saw the blackness in their place). Dark warm air embraced my shoulders. In the darkness the sky merged with the sea, and the sea with the mainland, and small lights shone at the top and the bottom. I stretched out my hands to them and swore that I would love you forever. Then I began to descend.

The descent from the mountain caused me great difficulty because of the ever-changing darkness. I was surprised at myself that I didn’t think of how dangerous a descent could be in the darkness. But soon I got out on the serpentine path, almost at the same time that the moon peeked through the clouds. While I was looking at it, I thought about all of those faces or rabbit’s likenesses that some found in the moon. At that moment it seemed to me that the moon indeed had a face, and now it was cheerfully looking at me. I hastened my pace, because I decided to call you in Berlin from Corinth before it got too late.

But it was already too late.

I don’t know what happened during those days, but something definitely did. You spoke absently; you didn’t ask me anything, and I had to hang up without saying much, but I wanted to tell you so many things. I decided to postpone our conversation until my return to Berlin. I thought that by this time your strange mood would pass (and at the same time something told me no, it wouldn’t pass, something changed and it changed forever). But I decided to follow my chosen path, without turning away; and if by now it turned out that my way didn’t make sense, it wasn’t as if I wasn’t aware of it then. I could guess, and I was happy and sad at the same time because I knew that I was doomed.

DISCLAIMER

Featured picture by Jenn Jones